MvR born

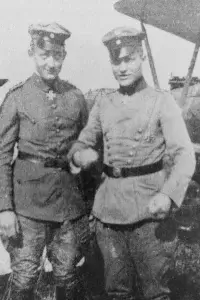

Der rote Kampfflieger von Rittmeister Manfred Freiherrn von Richthofen, 1917, 351.000 - 400.000, Verlag Ullstein & Co, Berlin-Wien p. 10

‘Now about my youth. The old man was in Breslau with the Leibkürasseren 1 when I was born on 2 May 1892. We lived in Kleinburg.’

Manfred von Richthofen, two years old

Die Erinnerungen der Mutter des roten Kampffliegers Kunigunde Freifrau von Richthofen. Im Verlag Ullstein - Berlin, 1937. p. 8

“This picture shows Manfred von Richthofen as a child, about two or three years old.”

Manfred von Richthofen is seven years old

Die Erinnerungen der Mutter des roten Kampffliegers Kunigunde Freifrau von Richthofen. Im Verlag Ullstein - Berlin, 1937. p. 8

“This picture shows Manfred von Richthofen as a child, around the age of seven. He is wearing a sailor suit, which was very fashionable at the time.”

MvR eight years old

Der rote Kampfflieger von Rittmeister Manfred Freiherrn von Richthofen, 1933, Eingeleitet und ergänzt von Bolko Freiherr von Richthofen, mit einem Vorwort von Generalfeldmarschall Hermann Göring, Verlag Ullstein & Co, Berlin p.

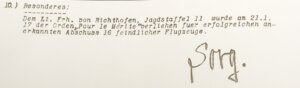

“When he was eight years old, he climbed the largest apple trees on the estate, which hardly anyone else could reach. But then he didn’t let himself down from the trunk, but from the outside on the branches, grasping them with the greatest dexterity. My parents often watched him do this, but never had the feeling that anything could happen to him, so sure were all his movements. My mother was never at all anxious with us boys. She was of the opinion that children could only be really skilful and able to cope with all dangers if they were given every conceivable physical freedom of movement. Only then would they be able to judge as accurately as possible what they could trust themselves to do. Of course, this has not always been without incident, but nothing more serious has ever happened.”

I did that myself

Der rote Kampfflieger von Rittmeister Manfred Freiherrn von Richthofen, 1933, Eingeleitet und ergänzt von Bolko Freiherr von Richthofen, mit einem Vorwort von Generalfeldmarschall Hermann Göring, Verlag Ullstein & Co, Berlin p.

“Because from the earliest days of his youth, Manfred had already shown samples of unusual energy. As an eight-year-old boy, my parents were expecting him one day from the railway in Wroclaw. He was to return from a long stay in the country with two large suitcases. The boy was sent to the railway station to be picked up and returned alone. Manfred was nowhere to be found. What had happened? There was no telephone back then. The excitement grew. While my parents were still discussing it, the doorbell rang and Manfred was standing safely at the door with both suitcases. ‘You must have taken a taxi?’. ‘No, I didn’t have any money.’ ‘Who carried the suitcases for you?’ ‘I did that myself.’

My parents were speechless and incredulous, because the suitcases were so heavy that Manfred would have had trouble lifting just one. But then they got the answer. ‘I was already able to lift one, I always carried it a bit and looked after the other one in the meantime, then I picked up the second one, and that’s how I gradually got there, unfortunately it took a bit of time.’

And all this with such natural calm and confidence that even then my parents could confidently leave Manfred to look after himself on the whole.”

Mrs. von Richthofen on child development

The Red Knight of Germany, the story of Baron von Richthofen, Floyd Gibbons, 1927, 1959 Bantam Books p. 7

“An easily terrified mother is a great obstacle to the physical development of children,’ Mrs von Richthofen said. ‘When Manfred was a little boy, I believe many of my friends considered me rather a careless mother because I did not forbid the two boys to engage in some of the feats they liked, but I was then, and am still, convinced children can only become agile if they are allowed such freedom as will enable them to judge what they can safely demand of their bodies.”

The family has to sell Schloss Romberg due to financial troubles.

MvR's early years

Der rote Kampfflieger von Rittmeister Manfred Freiherrn von Richthofen, 1917, 351.000 - 400.000, Verlag Ullstein & Co, Berlin-Wien p. 10

“I had private lessons until I was nine years old.”

MvR moves to Swidnica

Der rote Kampfflieger von Rittmeister Manfred Freiherrn von Richthofen, 1917, 351.000 - 400.000, Verlag Ullstein & Co, Berlin-Wien p. 10

“then a year of school in Schweidnitz”,

A child of Schweidnitz

Der rote Kampfflieger von Rittmeister Manfred Freiherrn von Richthofen, 1917, 351.000 - 400.000, Verlag Ullstein & Co, Berlin-Wien p. 10

‘I later became a cadet in Wahlstatt. But the people of Schweidnitz regard me as a child of Schweidnitz. The cadet corps prepared me for my current profession and I then joined the 1st Uhlan Regiment.’

MvR joins military cadets in Wahlstatt

Der rote Kampfflieger von Rittmeister Manfred Freiherrn von Richthofen, 1917, 351.000 - 400.000, Verlag Ullstein & Co, Berlin-Wien p. 12

‘I joined the cadet corps as a young sixth-former. I wasn’t overly keen on being a cadet, but it was my father’s wish and so I wasn’t asked for much. The strict discipline and order was particularly difficult for such a young badger. I wasn’t particularly keen on lessons. I was never a great lumen. I always did as much as I needed to in order to be promoted, but I didn’t think I could do any more and I would have considered it nerdy if I had done better than ‘sufficient’ in class. The natural consequence of this was that my teachers didn’t hold me in high esteem. On the other hand, I liked sports: Gymnastics, playing football, etc., immensely. I don’t think there was a single wave I couldn’t do on the gymnastics bar. I was soon awarded several prizes by my commander. All the breakneck moves impressed me enormously. For example, one fine day I crawled up the famous church tower of Wahlstatt on the lightning conductor with my friend Frankenberg and tied a handkerchief to the top. I still remember exactly how difficult it was to get past the gutters. When I visited my little brother once, about ten years later, I could still see my handkerchief hanging at the top. My friend Frankenberg was the first victim of the war that I ever saw.’

At that time he wanted to be a great cavalry general

Der rote Kampfflieger von Rittmeister Manfred Freiherrn von Richthofen, 1933, Eingeleitet und ergänzt von Bolko Freiherr von Richthofen, mit einem Vorwort von Generalfeldmarschall Hermann Göring, Verlag Ullstein & Co, Berlin p.

“That’s how Manfred got through his time as a cadet, even though this type of education and youthful treatment didn’t suit him too well. But he gritted his teeth and never complained during all the holidays he spent at his parents’ house. However, he told me, his younger brother, on several occasions: ‘If you can, do without the pleasure, it’s not nice in the pub either, but it’s still better.’ Manfred had decided very early on that he wanted to be an officer, and he had probably always been determined to achieve extraordinary things in the career he had chosen. At that time, however, he was thinking of becoming a great cavalry general. Little did he realise that he would become the first not on terra firma, but in the skies.”

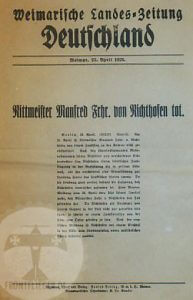

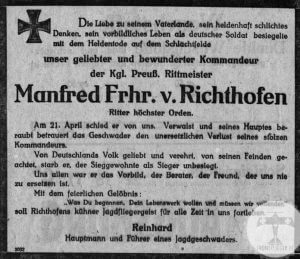

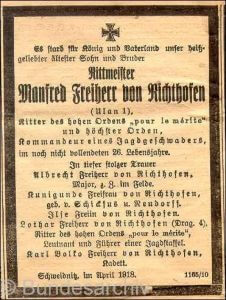

‘Captain Freiherr von Richthofen has not returned.’ So reports the army bulletin, succinctly and bluntly. So it has happened after all! What no one dared to think about has come to pass, what every German felt with quiet trepidation when Richthofen’s aerial victories reached the eerie height of eighty. The greatest flying ace of the World War died undefeated, a glorious death for the Kaiser and the Fatherland. An unspeakable pain pierces the hearts of our people at the loss of this bravest of the brave. As a true soldier, he rests in foreign soil where he fell. We were not granted the privilege of firing three volleys of honour over his grave. When I see the mighty towers of the venerable monastery church of Wahlstatt glimmering in the distance today, old, long-forgotten images come to mind. Richthofen and I wore the king’s uniform at the same time and were cadets at Wahlstatt. I had just joined the corps, a cheeky ten-year-old boy. Manfred Richthofen was several grades above me, and as a puny newbie, as the cadets called the newcomers, I would hardly have come into closer contact with him. But it did happen once – in a rather rough manner, which is now a fond memory for me. My room elder was a close friend of Richthofen’s, and he often sat in our room in the evenings. However, this friendship was clouded for some reason, so that both had pax ex, as we called it. Our room elder now tried to annoy Richthofen at every opportunity. Carnival had arrived, and the parcels from home with the eagerly awaited pancakes had arrived. The senior member of our room had had a huge jumping jack sent to him in the form of a life-size Negro, which aroused our greatest astonishment, for there were no carnival jokes or masquerades. But we soon guessed what was going on. One of us was supposed to secretly hang the Negro on Richthofen’s locker door. My blood was boiling at the time, and I was looking for an opportunity to distinguish myself. The bright red, grinning mouth of the negro, which stretched from ear to ear, was intended to provoke Richthofen – that was the main point! Manfred Richthofen had a full, strong mouth, which our dormitory leader always teased him about. We were sitting down to supper, so I sneaked out of the dining room as quickly as possible. I scurried across the company quarters with the negro I had fetched to the room where Richthofen was lying. Soon the snarling black man was dangling from the cupboard door, Richthofen’s nameplate emblazoned above his woolly head like an explanation. But the consequences were inevitable. Richthofen guessed where the negro had come from and also found out who had brought him. And then in the evening, I can still see it today, the door opened. Richthofen stood in the room, his steel-blue eyes, which meant nothing good for me at the time, searching the room. Now he had spotted me. The next moment he was standing in front of me – there was a crash on the left, a crash on the right – and then, as calmly as he had come, he left the room amid the respectful silence of his comrades. It is a strange memory! – That was the hand that later held the controls so firmly and sent eighty enemies to their deaths!”

Knee injury in the cadet corps

Der rote Kampfflieger von Rittmeister Manfred Freiherrn von Richthofen, 1933, Eingeleitet und ergänzt von Bolko Freiherr von Richthofen, mit einem Vorwort von Generalfeldmarschall Hermann Göring, Verlag Ullstein & Co, Berlin p.

“Manfred only caused my parents serious concern once. He had suffered a serious knee injury in the cadet corps. A piece of cartilage in his knee had torn loose during a fall squat without assistance. This piece occasionally became wedged between the kneecap, causing the leg to fold to one side without any willpower. Massages and all kinds of cures didn’t help; years and days went by and the leg wouldn’t get better. When my parents were once again discussing what to do, and my mother in particular was very depressed, Manfred wanted to comfort her and said: ‘If I can no longer walk on my legs, I’ll walk on my hands!’. And like a completely healthy person, he stretched both legs into the air and walked around the room on his hands. In the end, however, the decision was made to operate. Fortunately, this was successful and restored him to full health within a few weeks.”

Birthday of Kaiser Wilhelm II

Die Erinnerungen der Mutter des roten Kampffliegers Kunigunde Freifrau von Richthofen. Im Verlag Ullstein - Berlin, 1937. p. 52

“Twelve years ago, Manfred had travelled this route and I had visited him many times. I really liked the spirit of the school. The boys had to study hard, but they looked healthy because they did gymnastics diligently (Manfred’s strong side). When he was still a toddler, it was no trouble at all for him to shoot rumps from a standing position, and he never needed his hands to do so, but placed them tightly against the seam of the yard. He had a wonderfully skilful body by nature. Once, when he was eight years old, he had to take apples from an old, hard-to-reach fruit tree. He scrambled up like a little man of the woods and didn’t come down the trunk afterwards, no, that way was too boring for him; instead he let himself down on the outside of the branches, swinging and grabbing from branch to branch with lightning-like speed. These gymnastic skills stood him in good stead at the cadet school. He was honoured several times. There was also a lot of fun for us adults here in Wahlstatt. Once I went along to an imperial birthday party. Beforehand, Manfred had explained the following to me with a serious face: ‘You know, Mum, the cadets like to dance with every lady who still looks a bit young and pretty…only with the old and ugly mothers – the officers dance with them.’ Intimidated by these unsuccessful but life-knowledgeable openings, I asked my cadet son what I should wear to make myself desirable. ‘Well, a really light-coloured dress with a pretty flower on the belt.’ I took this to heart and was curious to see whether the gentlemen cadets would also like me. But – I was lucky, they danced with me first and not the officers. As a thank you, we then let our young cavaliers indulge in pancakes. What were the giant snuffles of these fragrant bales back then? That was something for Manfred – his favourite pastry; he was very reluctant to eat meat, preferring bread and cake instead.”

Manfred was extremely truthful

Der rote Kampfflieger von Rittmeister Manfred Freiherrn von Richthofen, 1933, Eingeleitet und ergänzt von Bolko Freiherr von Richthofen, mit einem Vorwort von Generalfeldmarschall Hermann Göring, Verlag Ullstein & Co, Berlin p. 21

“Manfred was extremely truthful. Even today, my mother cannot praise the extent to which my parents could always rely on him. He gave precise and clear answers to every question, regardless of what the consequences might be for him. As a twelve-year-old boy, he was once unable to curb his passion for hunting on his grandmother’s estate. When he couldn’t find any wild ducks on the Weistritz, he shot some tame ones, which were then missing from his grandmother’s duck pen. Manfred was put under strict interrogation, but it only lasted half a minute. It didn’t occur to him to deny or even gloss over what he had done. And the good grandmother gladly forgave her grandson, who could not lie. Manfred’s first ‘hunting trophies’, three drake feathers, still hang in his parlour in Schweidnitz today. Visitors will not be able to look at them without emotion. Manfred’s mother summarised these feelings and this conviction of Manfred’s nature in the short words: ‘He stood firm, wherever he was placed.’ This belief in his own ability, coupled with inner nobility and self-evident modesty, enabled my brother, I believe, to be a real leader. His Uhlans, when he was a lieutenant, and later all his subordinates in the Richthofen fighter squadron could trust him implicitly. He did not flatter them, but he protected them and kept his word, and serving under him was made easier by the cheerfulness and cheerfulness, indeed often by the exuberance with which he showed himself equal to even the most difficult tasks. For in one thing he was a perhaps unparalleled example to all who had to follow him in war: in the bravery of his spirit, in the absolute lack of any fear, indeed in the complete impossibility of being able to imagine any process or impending event that could be associated with any feeling of fear for him.”

The manor house is haunted

Der rote Kampfflieger von Rittmeister Manfred Freiherrn von Richthofen, 1933, Eingeleitet und ergänzt von Bolko Freiherr von Richthofen, mit einem Vorwort von Generalfeldmarschall Hermann Göring, Verlag Ullstein & Co, Berlin p. 23

“He didn’t underestimate the danger, but it didn’t play a role in his life. That was the case from an early age. The girls claimed that the manor house was haunted. A servant had once hanged himself on the floor upstairs and it had been haunted ever since, so they said in the servants’ parlour. Thirteen-year-old Manfred wanted to experience this haunting. He asked to be shown the exact spot on the floor where the accident had happened and had his bed carried to the spot to sleep. My mother knew Manfred’s fearlessness, but she decided to put him to the test. She crept upstairs with my sister and gradually began to roll chestnuts along the floor. At first Manfred slept soundly. But the thumping increased. Then he suddenly woke up, jumped up, grabbed a truncheon and lunged at the troublemakers. My mum had to switch on the light quickly, otherwise she would have had a bad time. But there was no sign of fear in Manfred. And that didn’t change until his last flight, from which he was never to return alive to his squadron and his own.”

MvR joins military cadets in Lichterfelde

Der rote Kampfflieger von Rittmeister Manfred Freiherrn von Richthofen, 1917, 351.000 - 400.000, Verlag Ullstein & Co, Berlin-Wien p. 13

‘I liked it a lot better in Lichterfelde. I was no longer so cut off from the world and began to live a little more as a person. My favourite memories from Lichterfelde are the big corso games, where I fought a lot with and against Prince Friedrich Karl. The prince won many a first prize back then. In races, football matches, etc. against me, who had not trained my body to such perfection as he had.’

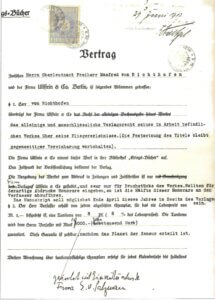

hunting trophy

Richthofen, der beste Jagdflieger des großen Krieges, Italiaander, A. Weichert Verlag, Berlin, 1938 p. 132

“It is hereby certified that His Royal Prussian Cadet Manfred Freiherr von Richthofen, in the presence of over 100 witnesses, most of whom are of impeccable character, shot and killed 20 hares and 1 pheasant (male) with his own hands today on the Jordansmühl field. The accuracy of this statement is certified by (many names follow).”

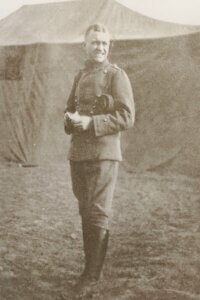

MvR joins Ulanen-Regiment „Kaiser Alexander III. von Rußland“ (Westpreußisches) Nr. 1

Der rote Kampfflieger von Rittmeister Manfred Freiherrn von Richthofen, 1917, 351.000 - 400.000, Verlag Ullstein & Co, Berlin-Wien p. 14

‘Of course, I could hardly wait to join the army. That’s why I went to the front after my midshipman’s examination and joined the Uhlan Regiment No. 1 ‘Kaiser Alexander III’. I had chosen this regiment; it was in my beloved Silesia and I had some friends and relatives there who strongly recommended it to me, and I really enjoyed serving with my regiment. It’s the best thing for a young soldier to be a ‘cavalryman’. I can’t really say much about my time at war school. It reminded me too much of the cadet corps and, as a result, I don’t have very fond memories of it. I did experience one funny thing. One of my war school teachers bought himself a really nice fat mare. The only flaw was that she was a bit old. He bought her for fifteen years. She had slightly thick legs. But otherwise she jumped excellently. I rode her a lot. She went under the name ‘Biffy’.’

MvR on the hunt

Die Erinnerungen der Mutter des roten Kampffliegers Kunigunde Freifrau von Richthofen. Im Verlag Ullstein - Berlin, 1937. p. 130

‘A memory came back to me. Even when Manfred was attending war college in Gdansk, he had hunted in East Prussia, and something happened at that time that got me excited. In the evening, his gamekeeper had shown him the hunting ground where he was to shoot a buck the next morning. Should he be given a hunter with him? No, thanks, he – Manfred – would find the stalking path on his own. The next morning is pitch dark. Manfred misses the direction in the darkness. He has completely lost his way in the large forest. Finally he arrives at a farmstead that lies alone in the forest. Here he has to ask for directions. The inhabitants are still fast asleep, no smoke curls over the moss-covered roof. Manfred knocks on a window, the dogs bark. Suddenly a gate opens and at the same moment two shots ring out. The coarse shot rattles in his ears. He had been mistaken for a burglar. Fortunately, the mistake was soon cleared up. The strange hunter was kindly shown the way and the buck was there for breakfast.’

Biffy

Der rote Kampfflieger von Rittmeister Manfred Freiherrn von Richthofen, 1917, 351.000 - 400.000, Verlag Ullstein & Co, Berlin-Wien p. 14

‘About a year later at the regiment, my Rittmeister v. Tr., who was very fond of sport, told me that he had bought a very chunky jumper. We were all very excited about the ‘chunky jumper’, who bore the rare name ‘Biffy’. I no longer thought about my war school teacher’s old mare. One fine day the wonder animal arrived, and now imagine the astonishment that good old ‘Biffy’ found herself back in Tr’s stable at the age of eight. She had changed hands several times in the meantime and her price had risen considerably. My war school teacher had bought her for fifteen hundred marks, and v. Tr. had bought her after a year as an eight-year-old for three thousand five hundred marks. She didn’t win any more jumping competitions, but she found a buyer again – and was killed right at the beginning of the war.’

“MvR appointed Leutnant and in the 3rd squadron in Ostrowo”

First period as an officer

Der rote Kampfflieger von Rittmeister Manfred Freiherrn von Richthofen, 1917, 351.000 - 400.000, Verlag Ullstein & Co, Berlin-Wien p. 16

‘I finally got the epaulettes. It was about the proudest feeling I’ve ever had to be called ‘Mr Lieutenant’ all at once. My father bought me a very beautiful mare called ‘Santuzza’. She was a marvellous animal and indestructible. Walked like a lamb in front of the train. I gradually discovered that she had great jumping ability. I immediately decided to make a show jumper out of this good mare. She jumped marvellously. I jumped a paddock trick of one metre sixty centimetres with her myself. I found a great deal of support and understanding from my mate von Wedel, who had won many a nice prize with his chargen horse ‘Fandango’. So we both trained for a show jumping competition and a cross-country ride in Breslau. ‘Fandango’ did brilliantly, ‘Santuzza’ tried hard and also did well. I had the prospect of doing something with her. The day before she was loaded, I couldn’t resist taking her over all the obstacles in our jumping garden again. We slipped and slid. Santuzza’ bruised her shoulder a little and I banged my collarbone. I also demanded speed from my good fat mare ‘Santuzza’ in training and was very surprised when von Wedel’s thoroughbred beat her. Another time I was lucky enough to ride a very nice chestnut at the Olympics in Wroclaw. The cross-country started and my gelding was still alive and kicking in the second third, so I had a chance of success. Then came the last obstacle. I could see from a distance that this must be something very special, as a huge amount of people had gathered there. I thought to myself: ‘Take courage, things will go wrong!’ and came hurtling up the embankment, on which stood a paddock trick. The crowd kept waving at me to stop riding so fast, but I couldn’t see or hear anything. My chestnut takes the paddock trick at the top of the dam and, to my utter amazement, it goes into the Weistritz on the other side. Before I knew it, the animal jumped down the slope in one giant leap and horse and rider disappeared into the water. Of course we went ‘overhead’. ‘Felix’ came out on this side and Manfred on the other. When they weighed me back at the end of the cross-country ride, they were astonished to see that I hadn’t lost the usual two pounds, but had gained ten pounds. Thank goodness you couldn’t tell that I was soaking wet. I also had a very good Charger and this unfortunate animal had to do everything. Running races, cross-country riding, jumping competitions, walking in front of the train, in short, there was no exercise in which the good animal was not trained. That was my well-behaved ‘Blume’. I had very nice successes on her. My last was in the Kaiserpreis-Ritt in 1913, when I was the only one to complete the cross-country course without making a mistake. One thing happened to me that won’t be repeated so easily. I galloped over a heath and was suddenly upside down. The horse had stepped into a hole in the harness and I had broken my collarbone in the fall. I’d ridden another seventy kilometres, hadn’t made a mistake and had kept time.’

Passion for equestrian sports

Der rote Kampfflieger von Rittmeister Manfred Freiherrn von Richthofen, 1933, Eingeleitet und ergänzt von Bolko Freiherr von Richthofen, mit einem Vorwort von Generalfeldmarschall Hermann Göring, Verlag Ullstein & Co, Berlin p.

“When Manfred was commissioned as a junior officer in the Ulan Regiment No. 1, Emperor Alexander III, he became even more passionate about equestrian sports than before. After he had received his officer’s licence, our father bought him a very beautiful mare. Manfred often praised this horse to me as a true marvel and indestructible. She walked like a lamb in front of his train and jumped at least one metre sixty.”

MvR participates in a horse race.

Manfred von Richthofen, The man and the aircraft he flew, David Baker, 1990, Outline Press p. 10

“On becoming a Lieutenant in 1912, Manfred’s father gave him a fine mare which he called Santuzza. The life of a young officer in a regiment of Uhlans reqired him to excel on horseback and von Richthofen actively participated in jumps and races, gaining several prizes but collecting a broken collar bone in the Kaiser Prize Race of 1913.”

Kaiserpreisritt

Der rote Kampfflieger von Rittmeister Manfred Freiherrn von Richthofen, 1933, Eingeleitet und ergänzt von Bolko Freiherr von Richthofen, mit einem Vorwort von Generalfeldmarschall Hermann Göring, Verlag Ullstein & Co, Berlin p.

“Manfred has won many great prizes in show jumping competitions and cross-country rides. Most recently in the Kaiserpreisritt in 1913.”

No racing, instead war

Der rote Kampfflieger von Rittmeister Manfred Freiherrn von Richthofen, 1933, Eingeleitet und ergänzt von Bolko Freiherr von Richthofen, mit einem Vorwort von Generalfeldmarschall Hermann Göring, Verlag Ullstein & Co, Berlin p.

“His ambition was to ride in big races in Breslau and in the capital of the Reich. For this purpose he had acquired a thoroughbred named Antithesis. But on the same day that the first race was to be run with his horse, he rode it across the Russian border. He would certainly have ridden many a horse to victory in many a race.”

War outbreak and journey from Zoppot to Schweidnitz.

Die Erinnerungen der Mutter des roten Kampffliegers Kunigunde Freifrau von Richthofen. Im Verlag Ullstein - Berlin, 1937. p. 7

“It was a summer’s day, as beautiful as it could be. The strong sun lay over the water. From the terrace of the beach hotel, over the burning red geraniums, we looked out over the deep blue sea. Our eyes followed the sailors gliding past like white shadows. The wind carried the sounds of the spa band. We had become very silent. I found myself in a strangely oppressive mood, as if on the border between dream and reality. Certainly, there were the slender figures of the two war pupils before me, their boyish, tanned faces under their paler foreheads, in which early masculinity already lay – there was Ilse’s bright, blooming appearance in summery white; but also her hearty, always laughing cheerfulness had fallen silent – there on the chair, which was pulled close to the table, sat Bolko, the youngest, and had the use of the fact that we adults did not eat from the cake and the pie. I took in this picture and looked again at the water, over which the narrow sails swayed, and into the glass of the sky and thought that it could not be that this picture was deceptive and that it would dissolve into nothing before what was now coming, before the Great Unknown, which, no one knew how, announced itself through everyone’s mouth: War…! Gottfried, the nephew, looked straight ahead, cool and matter-of-fact, as if he were at roll call. He said quite unexpectedly: ‘You have to take two pairs of woollen stockings with you’, and he named this and that exactly according to the regulations, which was part of the equipment when a young soldier goes into the field. This childlike soldierly fervour made me smile at all the conflicting feelings. I tried to read my son’s expression, but Lothar turned his narrow face with the very dark brows that had grown together over his nose. He didn’t want to speak now, only his bronze-coloured eyes occasionally flashed with the strong excitement that was working in him. Certainly his whole being, which otherwise seemed to be made for the joy of life, was seized. But he looked away, he didn’t want me to see what he was feeling and thinking. Only Bolko – blond, rosy-cheeked, childhood in a white sailor suit – continued to feast on the delicacies that this hour had given him, in which the Great Unknown stripped us of all the pleasure and carelessness that had gone before…Should we leave? Some bathers had already left Sopot – in an unnecessary hurry, it seemed. We also had to make a decision, I felt. If only someone could guess now! ‘You should ask Manfred.’ Lothar had said it. And he was certainly right. I saw the calm, almost indifferent face of my eldest in front of me. I could feel the certainty that emanated from him. I remembered how much I had felt the need to discuss all matters of importance with him, and how he always knew how to say and advise on the essentials, even in difficult matters, with a rationality that was hardly in keeping with his youth. ‘Why don’t you telegraph him?’ Lothar was right, especially as Manfred was with the detached squadron on the border, in Ostrowo, and was most likely to have wind of what was happening. I wrote a few words on a piece of paper and handed over the telegram for promotion. The two young soldiers exchanged a glance and stood up at the same time. The hour of separation had come. We went out onto the seafront. Many people were there, and their countenances were changed. A feverish, highly tense expectation vibrated in them. Was it the great unknown? A deep humming, such as I had never heard before, went through everyone. The band beamed with patriotic songs. Again and again they were called upon to play them. It was hard to escape the atmosphere. We made it to the hotel with great difficulty. Manfred’s reply arrived: ‘Advise you to leave.’ Now everything was clear, we packed. The phone went off. Lothar’s voice answered from Gdansk. And now this: ‘Farewell…goodbye…dear mum…’ These words resonated with me for a long time. On Friday, 31 July 1914, early in the morning, we travelled from Sopot to Silesia.”

Outbreak of war

Der rote Kampfflieger von Rittmeister Manfred Freiherrn von Richthofen, 1917, 351.000 - 400.000, Verlag Ullstein & Co, Berlin-Wien p. 19

‘There was nothing in all the newspapers but thick novels about the war. But we’d been used to the howls of war for a few months now. We had already packed our service cases so often that people were bored and no longer believed in war. But least of all did we believe in war, as we were the first on the frontier, the ‘eye of the army’, as my commanding officer had called us cavalry patrols at the time. On the eve of the increased readiness for war, we sat with the detached squadron, ten kilometres from the border, in our mess, ate oysters, drank champagne and played a little. We were very amused. As I said, nobody was thinking about war. Wedel’s mother had already made us a little suspicious a few days earlier; she had come from Pomerania to see her son again before the war. As she found us in a very pleasant mood and realised that we weren’t thinking about war, she couldn’t help but invite us to a decent breakfast. We were just enjoying ourselves when suddenly the door opened and Count Kospoth, the District Administrator of Öls, stood on the threshold. The count made an astonished face. We greeted the old acquaintance with a hello and he explained the purpose of his journey, namely that he wanted to see for himself at the border what was true about the rumours of the approaching world war. He quite rightly assumed that those on the border should know best. Now he was quite astonished at the picture of peace. Through him we learnt that all the bridges in Silesia were guarded and that they were already thinking of fortifying individual places. We quickly convinced him that war had been ruled out and continued our celebrations. The next day we moved into the field.’

War outbreak, the first days

Die Erinnerungen der Mutter des roten Kampffliegers Kunigunde Freifrau von Richthofen. Im Verlag Ullstein - Berlin, 1937. p. 9

“Thank God that this journey is behind us. The crowds at the station were life-threatening, the train unimaginably overcrowded. We jumped into the departing train with more desperation than courage – and, of course, illegally – and were so lucky to be taken along. Our triumph was complete when we finally managed to get three seats in the dining car. The train travelled very slowly, almost sluggishly. All the bridges were under military guard, the first vague hint of war. Wroclaw! From here on to Schweidnitz – without a ticket, without luggage. Exhausted, we arrived in front of our house. Outside, under the tall trees in front of the gate, my husband walked up to us with heavy steps. ‘We’re coming back – because there’s a war.’ ‘War?’ No, I didn’t believe in it. Who could take on such responsibility?”

He leaves the following lines to his parents and siblings:

Richthofen, der beste Jagdflieger des großen Krieges, Italiaander, A. Weichert Verlag, Berlin, 1938 p. 70

“Ostrowo, 2 August 1914. These are my last lines in great haste. My warmest greetings to you. Should we not meet again, please accept my heartfelt thanks for everything you have done for me. I have no debts, even a few hundred marks more, which I am taking with me. Your grateful and obedient son and brother Manfred embraces each and every one of you.”

War outbreak, the first days

Die Erinnerungen der Mutter des roten Kampffliegers Kunigunde Freifrau von Richthofen. Im Verlag Ullstein - Berlin, 1937. p. 9

“On 2 August, the mobilisation order was followed by the declaration of war. Lothar returned from the war college in Danzig to his regiment, the 4th Dragoons in Lüben. And Manfred? While the garrison here presented a feverishly moving picture in an unexpected abundance of people and thoughts were still buzzing about what would happen, he rode as a young Uhlan lieutenant against the enemy in the east. And under him walked ‘Antithesis’, the English thoroughbred that I had given to him, the well-travelled, passionate rider. On the same day that it was to carry him to victory on the racecourse in Poznan, it carried him across the border – on patrol against Russia.”

Crossing the border

Der rote Kampfflieger von Rittmeister Manfred Freiherrn von Richthofen, 1917, 351.000 - 400.000, Verlag Ullstein & Co, Berlin-Wien p. 21

‘We border cavalrymen were familiar with the word ‘war’. Everyone knew exactly what to do and what not to do. But no one had any real idea what would happen next. Every active soldier was happy to finally be able to show his personality and skills. We young cavalry lieutenants were probably given the most interesting tasks: reconnaissance, getting into the enemy’s rear, destroying important installations; all tasks that demanded a whole man. With my mission in my pocket, the importance of which I had been convinced of through long study for a year, I rode at twelve o’clock at night at the head of my patrol for the first time against the enemy, the border was a river, and I could expect to receive fire there for the first time. I was quite astonished how I was able to pass the bridge without incident. The next morning, without further incident, we reached the church tower of the village of Kielcze, which I knew well from riding along the border. Everything had passed off without me noticing an enemy, or rather without being noticed myself. How was I supposed to ensure that the villagers didn’t notice much? My first thought was to put the popes under lock and key. So we took the completely surprised and highly perplexed man out of his house. I locked him in the belfry of the church tower, removed the ladder and let him sit at the top. I assured him that if even the slightest hostile behaviour on the part of the population should make itself felt, he would immediately be a child of death. A sentry kept a lookout from the tower and watched the area. I had to send daily reports by patrol riders. My small group of dispatch riders soon dispersed, so that I finally had to take over the last dispatch ride as the messenger myself. Everything remained quiet until the fifth night. On this night, the sentry suddenly came running to me at the church tower – I had stabled my horses near it – and called out to me: ‘Cossacks are here!’. It was pitch dark, a bit rainy, no stars. You couldn’t see your hand in front of your eyes. We led the horses through a breach that had been cut through the churchyard wall as a precaution into the open field. There, because of the darkness, we were completely safe after fifty metres. I myself went with the sentry, carbine in hand, to the designated place where the Cossacks were supposed to be. I crept along the wall of the churchyard and came to the road. That made me feel a bit uneasy, because the whole village was swarming with Cossacks. I looked over the wall behind which the guys had their horses. Most of them had blinding lanterns and were behaving very carelessly and loudly. I estimated there were about twenty to thirty of them. One had done his time and gone to the priest, whom I had released from prison the day before. Treason, of course! it flashed through my brain. So be doubly careful. I couldn’t let it come to a fight, because I didn’t have more than two carbines at my disposal. So I played ‘cops and robbers’. After a few hours’ rest, the visitors rode off again. The next morning, however, I decided to make a small change of quarters. On the seventh day I was back in my garrison and everyone stared at me as if I were a ghost. This was not because of my unshaven face, but rather because rumours had spread that Wedel and I had fallen near Kalisch. People knew the exact time, place and circumstances so well that the rumour had already spread throughout Silesia. Even my mother had already received visits of condolence. The only thing missing was a death notice in the newspaper. A funny story happened at the same time. A horse doctor was ordered to requisition horses from a farmstead with ten Uhlans. It was about three kilometres away. He returned from his mission quite excited and reported the following: ‘I was riding across a stubble field where the dolls were standing, when suddenly I recognised enemy infantry some distance away. Without further ado I draw my sabre and shout to my Uhlans: ‘Lance down, charge, march, march, hurrah! The men are enjoying themselves and a wild rush across the stubble begins. But the enemy infantry turn out to be a pack of deer that I had misjudged in my short-sightedness.’ The capable gentleman suffered from his attack for a long time.’

War outbreak, the first days

Die Erinnerungen der Mutter des roten Kampffliegers Kunigunde Freifrau von Richthofen. Im Verlag Ullstein - Berlin, 1937. p. 10

“On 3 August we learned that the Uhlan Regiment 1 and the Infantry Regiment 155 had occupied Kalisch. The first battle – the first success. And: Manfred was there. A proud feeling, despite all the worries.”

MvR writes from Schelmce

Die Erinnerungen der Mutter des roten Kampffliegers Kunigunde Freifrau von Richthofen. Im Verlag Ullstein - Berlin, 1937. p. 11

“Manfred wrote from Schelmce, on the other side of the border. The letter was dated 5 August, the day when the church service brought us together on the little parade ground and I was worried about him. While we stood and sang, he probably wrote this greeting to home in some forest clearing south-west of Kalisch, with the distant rumble of the cannons, still tired from the night patrol, which is now his third. Only six men still belong to the small troop of horsemen that has closed in on the enemy. None of them are wounded yet, thank goodness. But things will probably change soon. When I receive this letter, Manfred writes, he may already be on his way to the west. Lothar also wrote a card from Traben about the journey there. We have never been able to say goodbye to either of our sons. That’s a little sad. But how many mothers will feel like that!”

MvR should be dead

Die Erinnerungen der Mutter des roten Kampffliegers Kunigunde Freifrau von Richthofen. Im Verlag Ullstein - Berlin, 1937. p. 10

“Today was a day that is still fresh in my mind, but which also moved me deeply. A field service was held for the entire garrison, the soldiers and their families on the small parade ground, which is so pleasantly lined with greenery on two sides, very close to our house. It was a great farewell in the face of the eternal, a togetherness that only fate can create, which must now be borne indissolubly by all. Even before the service began, England’s declaration of war on Germany had become known. There they stood now, our soldiers, who were our pride, like walls they stood on three sides of the square, on the still free flank the men and women in dark clothes, the parents, the sisters of our warriors, who would leave today in grey dress, tomorrow or the day after tomorrow. In the centre stood the field altar, with clergymen speaking, deep seriousness on all faces; one tried to remember this or that image that had become dear to one from happier days. Perhaps you would never see it again. The sky arched blue and cloudless over the solemn, beautiful picture, the light wind carried the humming of the church bells, we all sang ‘We come to pray…’ with great fervour. It was like a pledge, it shone through us all, and everyone felt: for the German people there is only victory – or doom. And now something happened to me that I couldn’t believe. Acquaintances who greeted us did so with such shy cordiality that I was finally taken aback. They asked about Manfred, again and again, with such strange sympathy. Had my son returned from the patrol battles on the other side of the border? ‘Yes, certainly…’ But why was everyone asking so strangely, my God. What had happened? My knees became weak, they pushed me a field chair and I had to sit down. Then I heard that Manfred was dead and that his friend Webel was also missing or killed. Fear tightened my heart, but only for a moment. A certainty, a confidence that was based on nothing but itself, told me: it can’t be, it’s all a mistake, he’s alive. And this trust in the inner voice had the effect that all anxiety fell away from me, that I soon became comforted, even cheerful…”

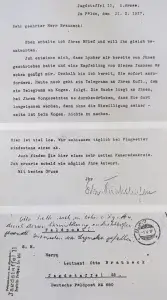

“Dear Mum!

How are you all doing in these turbulent times? You are certainly safest in Schweidnitz. I am now on my third night on patrol in Russia. There are no German troops ahead of me, so I am the furthest forward. One becomes brutalised in no time at all. I don’t mind that I haven’t taken off my clothes for four days and haven’t washed since the declaration of war. I sleep very little with my six men – under the open sky, of course. The nights are quite warm, but today, in the rain outside, it was less pleasant. There is little to eat; you have to fight to get anything. None of my men have been wounded yet. By the time you receive this letter, I may already be at the French border. The cannons have just thundered again from the direction of Kalisch, we’ll have to see what’s going on. Warm greetings to you all from nearby Russia

Yours, Manfred.”

Ilse's birthday

Die Erinnerungen der Mutter des roten Kampffliegers Kunigunde Freifrau von Richthofen. Im Verlag Ullstein - Berlin, 1937. p. 12

“Today was Ilse’s birthday. We didn’t celebrate it (who would have the sense for that now!). We used the day to sew the clothes she needs as a Red Cross carer. The formal dresses were packed in suitcases – they have no place at this time. Ilse is determined to help wherever she can, it’s in her active and happy nature. When things get serious and tough, we will need such companionable people. It’s really nice to see how much good will and willingness to act there is in our women. Everyone wants to contribute to the success of the great cause to the best of their ability. Many women and young girls go to all the military trains passing through the railway station to give the soldiers refreshments; rolls, sausages, cigarettes, malt beer and postcards are distributed. The last time I was at the railway station, the soldiers were already so full that they had to be literally forced to eat. There was only a constant demand for cigarettes and beer. One is downright grateful when the field grey expresses a wish that can be fulfilled. They should be aware that their homeland would like to do them all the good it can before they have to suffer the most terrible hardships. The garrison has now been stripped of its active troops. The 10th Grenadiers and the 42nd Artillery Regiment have also left. As they said, to the west. Nevertheless, the town presents an eventful and interesting picture. Instead of the usual taut, soldierly appearance, you can now see other faces, first individuals and then many, many others. The volunteers have appeared on the scene. I was very excited when I watched from the window as they marched through the streets singing; some of them still looked like boys to me, they hadn’t quite grown into their uniforms yet, they hadn’t been weaned from their parents’ house. But there was real enthusiasm in their eyes and in the way they marched singing, somewhat awkwardly but with great grit. – Our little servant Gustav Mohaupt also rushed to the flags and wrote how happy he was to have arrived with the hunters in Hirschberg. We live quietly and listen eagerly for any news from the theatre of war. The capture of Liège aroused great rejoicing. The newspapers caused an undoubted sensation with their reports that mysterious gold cars were on their way from France to Russia. This billion-dollar treasure on wheels slowly became a nuisance. Roads were closed, guards and firemen stopped every car. Here and there there were senseless and unfortunately not entirely bloodless bangs. It took tens of days for the psychosis to disappear. Instead, the bridge guards were increasingly nervous. Shots are heard almost every night. During the day, the most uncontrollable rumours run through the city. Yesterday, a pair of secret lovers, perhaps blinded by the bridge regulations, were the victims of the rules. ‘He’ got a good scare, ‘she’ a slight shot in the arm. Everything went off lightly. I received 700 marks from Manfred. He told me to keep it for him. He hadn’t left any debts behind him – he wrote – but had saved quite a bit. That’s just the way he is. His external and internal circumstances are always in such a state that he can give an account every hour. He is always clear, organised and ready.”

Towards Busendorf, Diedenhofen

Der rote Kampfflieger von Rittmeister Manfred Freiherrn von Richthofen, 1917, 351.000 - 400.000, Verlag Ullstein & Co, Berlin-Wien p. 25

‘To France. We were now loaded in my garrison town. Where to? – No idea whether west, east, south or north. There were a lot of rumours, but most of them were over. But in this case we probably had the right instinct: west. The four of us were allocated a second-class compartment. We had to stock up on provisions for a long train journey. Drinks were not missing, of course. But on the very first day we realised that a second-class compartment like that was pretty cramped for four young warriors, so we decided to spread out a bit more. I set up one half of a pack wagon as my living and sleeping quarters and had definitely done something good. I had air, light etc. I had procured straw from a station and the tent was covered on top of it. I slept as soundly in my sleeping car as if I were lying in my family bed in Ostrowo. The journey went on day and night, first through the whole of Silesia and Saxony, then more and more to the west. We seemed to be heading towards Metz; even the transport driver didn’t know where we were going. At every station, even where we didn’t stop, there was a sea of people who showered us with cheers and flowers. The German people were wildly enthusiastic about the war; you could tell. The Uhlans were particularly marvelled at. The platoon that had hurried through the station earlier must have spread the word that we had already been at the enemy – and we had only been at war for eight days – and my regiment had already been mentioned in the first army report: Uhlan Regiment 1 and Infantry Regiment 155 conquered Kalisch. So we were the celebrated heroes and felt like heroes. Wedel had found a Cossack sword and showed it to the astonished girls. It made a great impression. We claimed, of course, that there was blood on it, and made up a monstrous fairy tale about the peaceful sword of a gendarmerie chief. We were terribly exuberant. Until we were finally unloaded in Busendorf near Diedenhofen. Shortly before the train arrived, we stopped in a long tunnel. I have to say, it’s quite uncomfortable to stop suddenly in a tunnel in peacetime, but especially in wartime. Then an overconfident man took the liberty of joking and fired a shot. It didn’t take long before a wild shooting started in the tunnel. It is a miracle that nobody was injured. What caused it never came out.’

Through Luxemburg to Arlon

Der rote Kampfflieger von Rittmeister Manfred Freiherrn von Richthofen, 1917, 351.000 - 400.000, Verlag Ullstein & Co, Berlin-Wien p. 27

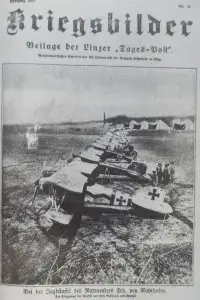

‘We unloaded in Busendorf. It was so hot that our horses threatened to fall over. For the next few days, we marched north towards Luxembourg. In the meantime, I had found out that my brother had ridden the same route with a cavalry division about eight days earlier. I was even able to track him again, but I didn’t see him until a year later. Nobody in Luxembourg knew how this little country behaved towards us. I still remember today how I saw a Luxembourg gendarme from afar, surrounded him with my patrol and wanted to capture him. He assured me that if I didn’t let him go immediately, he would complain to the German Emperor, which I realised and let the hero go. We passed through the city of Luxembourg and Esch and were now approaching the first fortified towns in Belgium. On the march there, our infantry, like our entire division in general, performed pure peacetime manoeuvres. We were terribly excited. But such a manoeuvre outpost picture was quite digestible from time to time. Otherwise we would definitely have gone over the top. Troops from various army corps were marching to the right and left, on every street, in front of and behind us. There was a feeling of chaos. Suddenly the confusion turned into a march that worked like a charm. I had no idea what our airmen were capable of back then. In any case, every airman gave me a tremendous dizziness. I couldn’t tell whether it was a German or an enemy plane, I didn’t even realise that the German planes carried crosses and the enemy planes carried circles. As a result, every aeroplane came under fire. The old pilots still talk today about how embarrassing it was for them to be shot at equally by friend and foe.’

Arlon

Der rote Kampfflieger von Rittmeister Manfred Freiherrn von Richthofen, 1917, 351.000 - 400.000, Verlag Ullstein & Co, Berlin-Wien p. 28

‘We marched and marched, the patrols far ahead, until one fine day we were at Arlon. I had a funny feeling as I crossed the border for the second time. I had already heard dark rumours of franchisers and the like. I had once been ordered to liaise with my cavalry division. I rode no less than one hundred and ten kilometres that day with my entire patrol. Not one horse was broken, a brilliant performance by my animals. In Arlon I climbed the church tower in accordance with the principles of peacetime tactics, but of course I saw nothing, because the evil enemy was still far away. People were still pretty harmless back then. For example, I had left my patrol outside the town and cycled through the town to the church tower all by myself. When I came back down, I was surrounded by a grumbling and muttering crowd of hostile-looking youths. My bike had been stolen, of course, and I now had to walk for half an hour. But I enjoyed it. I would have loved a little scuffle like that. I felt incredibly safe with my gun in my hand. As I learnt later, the inhabitants had behaved very riotously both against our cavalry a few days earlier and later against our military hospitals, and a whole lot of these gentlemen had had to be put up against the wall. I reached my destination in the afternoon and learnt there that my only cousin Richthofen had been killed three days earlier, in the very vicinity of Arlon. I stayed with the cavalry division for the rest of the day, took part in a blind alarm there and arrived at my regiment late at night. You experienced and saw more than the others, you’d been around the enemy before, you’d had to deal with the enemy, you’d seen the traces of war and were envied by everyone with a different weapon. It was too good, probably my best time in the whole war. I would like to take part in the beginning of the war again.’

Unfortunately, I rarely have time to write, and when I do, it is only briefly. Therefore, please do not be concerned if you do not hear from me for eight to fourteen days. I have not yet received a letter from you. I have experienced and seen a great deal. The war has already claimed the lives of many officers in our cavalry unit. The local residents are particularly hostile towards us. Wolfram was killed by them, and Lothar is also here in Belgium.

MvR writes from France

Die Erinnerungen der Mutter des roten Kampffliegers Kunigunde Freifrau von Richthofen. Im Verlag Ullstein - Berlin, 1937. p. 14

“Dear Mum, I received your last letter in Ostrowo dated 4 August. The field post doesn’t seem to be working very well. I write to you almost every day and always hope that the connection from me to you is better than the other way round. We Uhlans are unfortunately assigned to the infantry; I say unfortunately because Lothar has certainly already taken part in great cavalry battles, the likes of which we will hardly ever see. I am sent out on patrol a lot and am doing my best to come back with the Iron Cross. I think it will be another eight to fourteen days before we fight a big battle. “Antithesis is doing just great. He’s building out, ironclad, calm, jumping every Koppelrick and really doing everything as if he’s done nothing else so far, not getting leaner but fatter.‘’

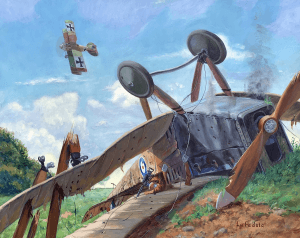

How I first heard the bullets whistle on patrol

Der rote Kampfflieger von Rittmeister Manfred Freiherrn von Richthofen, 1917, 351.000 - 400.000, Verlag Ullstein & Co, Berlin-Wien p. 31

‘I had the task of determining how strong the occupation of a large forest near Virton might be. I rode out with fifteen Uhlans and realised that today would be the first clash with the enemy. My mission was not an easy one, for there can be an awful lot in a forest like this without you being able to see it. I came over a height. A few hundred paces in front of me lay a huge forest complex of many thousands of acres. It was a beautiful August morning. The forest was so peaceful and quiet that I could no longer feel any thoughts of war. Now the top was approaching the entrance to the forest. You couldn’t see anything suspicious through the glass, so you had to ride up and wait to see if you could catch fire. The spike disappeared into the forest path. I was next, with one of my most capable Uhlans riding beside me. At the entrance to the forest was a lonely ranger’s hut. We rode past it. All at once a shot was fired from a window of the house. Immediately afterwards [32]another. I recognised at once from the bang that it was not a rifle shot, but that it came from a shotgun. At the same time I saw some disorder in my patrol and immediately suspected an attack by Franktireurs. One thing was to get off the horses and surround the house. In a somewhat dark room I recognised four or five lads with hostile eyes. Of course, there was no shotgun in sight. My anger was great at that moment; but I had never killed a man in my life, so I must say I was extremely uncomfortable at the moment. Actually, I should have shot the Franktireur down like a piece of cattle. He had fired a load of shot into the belly of one of my horses and wounded one of my Uhlans in the hand. I shouted at the gang in my poor French and threatened to shoot them all down if the culprit didn’t come forward immediately. They realised that I was serious and that I would not hesitate to put my words into action. I can’t remember how it actually happened. In any case, the marksmen were suddenly out of the back door and had disappeared from the face of the earth. I shot after them without hitting them. Luckily I had surrounded the house so that they couldn’t actually slip away. [I immediately had the house searched for them, but found no more. If the guards behind the house hadn’t been paying attention, the whole place was empty. We found the shotgun standing by the window and had to take our revenge in another way. In five minutes the whole house was on fire. After this intermezzo, we moved on. I recognised from fresh horse tracks that strong enemy cavalry must have marched directly in front of us. I stopped with my patrol, cheered them on with a few words and had the feeling that I could absolutely rely on every one of my lads. Everyone, I knew, would stand their ground in the next few minutes. Of course, none of them thought of anything other than an attack. It must be in the blood of a Teuton to run over the enemy wherever you meet him, especially enemy cavalry, of course. I could already see an enemy squadron at the head of my pack and was drunk with joyful anticipation. My Uhlans’ eyes flashed. So we continued at a brisk trot along the fresh track. After an hour’s sharp ride through the most beautiful mountain gorge, the forest became a little lighter and we approached the exit. I realised that I would run into the enemy. So [34]be careful! with all the attacking courage that inspired me. To the right of the narrow path was a steep rock face many metres high. To my left was a narrow mountain stream, then a meadow fifty metres wide, bordered by barbed wire. All of a sudden the horse track stopped and disappeared over a bridge into the bushes. I stopped at the top, because the forest exit was blocked by a barricade in front of us. I immediately realised that I had been ambushed. I suddenly recognised movement in the bushes behind the meadow to my left and could make out dismounted enemy cavalry. I estimated their strength at a hundred rifles. There was nothing to be wanted here. Straight ahead the way was blocked by the barricade, to the right were the rock walls, to the left the meadow fenced in with wire prevented me from my plan, the attack. There was no time to dismount and attack the enemy with carbines. So there was nothing left to do but fall back. I could have trusted my good Uhlans to do anything, but not to run away from the enemy. – That was to spoil the fun for many, because a second later the first shot rang out, followed by a furious rapid fire from the forest over there. The distance was about fifty to a hundred metres. The men were [35]instructed that if I raised my hand they were to join me quickly. Now I knew we had to go back, so I raised my arm and waved to my men. They must have misunderstood. My patrol, which I had left behind, thought I was in danger and came rushing up in a wild caracho to chop me out. All this took place on a narrow forest track, so you can imagine the mess that happened. My two lead riders lost their horses because of the raging fire in the narrow ravine, where the sound of each shot was multiplied tenfold, and I only saw them take the barricade in one jump. I never heard from them again. They are certainly in captivity. I myself turned round and gave my good ‘Antithesis’ the spurs, probably for the first time in his life. It was only with great difficulty that I was able to tell my Uhlans, who came rushing towards me, not to come any further. Turn round and away! My lad rode beside me. Suddenly his horse fell, I jumped over it and other horses rolled around me. In short, it was a chaotic mess. All I could see of my lad was how he lay under the horse, apparently not wounded, but tied up by the horse lying on him. The enemy [36]had taken us brilliantly by surprise. He had probably been watching us from the start and, as the French are apt to ambush their enemy, he had tried it again in this case. I was delighted when, two days later, I suddenly saw my boy standing in front of me, albeit half barefoot, as he had left one boot under his horse. He told me how he had escaped: at least two squadrons of French cuirassiers had later come out of the forest to plunder the many fallen horses and brave Uhlans. He had immediately jumped up, climbed the rock face unwounded and collapsed in a bush fifty metres up, completely exhausted. About two hours later, after the enemy had returned to his ambush, he had been able to continue his escape. After a few days he came back to me. He could say little about the whereabouts of the other comrades.’

MvR writes his mother

Die Erinnerungen der Mutter des roten Kampffliegers Kunigunde Freifrau von Richthofen. Im Verlag Ullstein - Berlin, 1937. p. 14

“The Hirschberg fighters have suffered heavy losses, 300 men are said to be dead or wounded. Manfred reported. In the afternoon news came of a great battle between Metz and the Vosges, in which the troops of the Crown Prince of Bavaria had defeated the French. The fleeing enemy is being pursued relentlessly. There is great joy here. Everything rushed into the town. There was great life at the market, but no details were given. The post office was flying flags.”

First battle - first retreat

The Red Knight of Germany, the story of Baron von Richthofen, Floyd Gibbons, 1927, 1959 Bantam Books p. 15

“It was on August 21st, in the little Belgian village of Etalle, twenty miles from the frontier, that Richthofen received orders to make a mounted reconnaissance toward the south in the direction of a little town called Meix-devant-Virton. His duty it was to discover the strenght of French cavalry supposed to be occupying a large forest. With the war less than two weeks old, movement marked the efforts of the opposing forces to get into advantageous contact with one another.”

Patrol ride with Loen

Der rote Kampfflieger von Rittmeister Manfred Freiherrn von Richthofen, 1917, 351.000 - 400.000, Verlag Ullstein & Co, Berlin-Wien p. 37

‘The battle of Virton was underway. My comrade Loen and I once again had to patrol to find out where the enemy had gone. We rode after the enemy all day, finally reached him and were able to write a decent report. In the evening, the big question was: should we ride through the night to get back to our troops, or should we conserve our strength and rest up for the next day? That’s the beauty of leaving the cavalry patrol completely free to act. So we decided to stay with the enemy for the night and ride on the next morning. According to our strategic view, the enemy was on the march back, and we pressed on after him. As a result, we were able to spend the night in relative peace. Not far from the enemy was a marvellous monastery with large stables, so that we were able to quarter both Loen and my patrol. However, the enemy was still sitting so close by towards evening, as we were sheltering there, that he could have shot us through the windows with rifle bullets. [The monks were extremely kind. They gave us as much food and drink as we wanted, and we enjoyed it very much. The horses were unsaddled and were quite happy to get their eighty kilos of dead weight off their backs for the first time in three days and three nights. In other words, we settled in as if we were on manoeuvres and having dinner with a dear friend. Incidentally, three days later several of the hosts were hanging from the lamppost, as they had not been able to resist taking part in the war. But that evening they were really very kind. We crawled into our beds in our nightgowns, put up a post and let the good Lord be a good man. At night, someone suddenly opened the door and the guard’s voice rang out: ‘Lieutenant, the French are here.’ I was too sleepy to even answer. Loen felt the same way and only asked the witty question: ‘How many are there?’ The post’s reply, very excited: ‘We’ve already shot two dead; we can’t say how many because it’s pitch dark.’ I hear Loen reply sleepily: ‘So if more come, you’ll wake me up.’ Half a minute later, we continued snoring. [39]The next morning, the sun was already quite high when we woke up from our sound sleep. After a hearty breakfast, we set off again. In fact, the French had marched past our castle during the night, and our guards had made a fire attack on them during this time. But as it was pitch dark, no major battle had resulted. We soon continued along a lively valley. We rode over the old battlefield of our division and were astonished to see only French medics instead of our men. French soldiers could still be seen from time to time. But they made just as stupid faces as we did. Nobody had thought about shooting. We then made ourselves thin as quickly as possible, because we were so slow that instead of going forwards, we had concentrated a little backwards. Luckily the enemy had run off to the other side, otherwise I’d be a prisoner somewhere. We passed through the village of Robelmont, where we had last seen our infantry in position the day before. There we met a local resident and asked him about the whereabouts of our soldiers. He was very happy and assured me that the Germans were ‘partis’. [40]We turned a corner and witnessed the following strange sight. In front of us there was a swarm of red trousers – I estimated about fifty to a hundred – eagerly endeavouring to smash their rifles on a cornerstone. Next to them were six grenadiers who, as it turned out, had captured the brothers. We helped them to remove the Frenchmen and learnt from the six grenadiers that we had started a rearward movement during the night. I reached my regiment late in the afternoon and was quite satisfied with the last twenty-four hours.’

“Dear Mum!

I want to briefly describe to you what I have experienced here in the West. – Before the army’s deployment was complete, it was of course quite boring. We were unloaded northeast of Diedenhofen and marched through Luxembourg, crossing the Belgian border at Arlon.

In Etalle, about twenty kilometres west of Arlon, I was given the order on 13 August to reconnoitre in a southerly direction towards Meix-devant-Virton. In Etalle, about twenty kilometres west of Arlon, I was ordered on 13 August to reconnoitre southwards towards Meix-devant-Virton. As I reached the edge of the forest south of Etalle, I spotted a squadron of French cuirassiers. I only had ten men with me. After about half an hour, the enemy squadron disappeared, and I set off after them to find out where they had gone, ending up in a huge mountainous forest. I was just at the edge of the forest near Meix-devant-Virton.

To my right is a rock face, to my left a stream, behind it a meadow about fifty metres wide – then the edge of the forest. Suddenly, my vanguard stops. I gallop ahead to see what is going on. Just as I raise my telescope to my eyes, a volley of shots rings out from the edge of the forest about fifty metres away and from the front. I found myself facing about two hundred to two hundred and fifty carbines. I couldn’t go left or forward because the enemy was there – to the right was the steep rock face, so I had to go back. Yes, if only it had been that simple. The path was very narrow and led straight past the edge of the forest occupied by the enemy, but what could I do? There was no time to think, so I went back. I was the last one. Despite my previous prohibition, everyone else had gathered together and presented the French with a good target. Perhaps that is the reason why I escaped. I brought back only four men. This baptism of fire was less fun than I had imagined. In the evening, a few more people returned whose horses had died and who had managed to save themselves on foot. It is truly a miracle that nothing happened to me and my horse.

That same night, I was sent to Virton, but did not get there because Virton was occupied by the enemy. During the night, Division Commander von Below decided to attack the enemy at Virton and appeared with his vanguard Ul-R. 1 at the edge of the forest. The fog was so thick that you couldn’t see thirty paces ahead. One regiment after another emerged from the narrow forest paths, as if in a manoeuvre. Prince Oskar stood on a pile of stones and had his regiment, the 7th Grenadiers, march past him, looking each grenadier in the eye. It was a magnificent moment before the battle. Thus came the Battle of Virton, where the 9th Division fought against an enemy six times its size, held out for two days and finally won a brilliant victory. In this battle, Prince Oskar led his regiment at the forefront and remained unharmed. I spoke to him afterwards, just as he was being presented with the Iron Cross.”

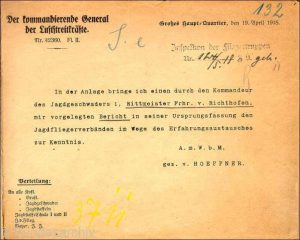

MvR appointed Ordonnanzsofficier.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_victories_of_Manfred_von_Richthofen p.

“On September 1, 1914, he was transferred as an intelligence officer to the 4th Army, which at that time was stationed in front of Verdun.”

MvR sends a card

Die Erinnerungen der Mutter des roten Kampffliegers Kunigunde Freifrau von Richthofen. Im Verlag Ullstein - Berlin, 1937. p. 17

“I received a card from Manfred. He is well and cheerful. I had to think about him a lot, but now I’m reassured and happy again. We had a war service in the church. It struck me how many people were already in mourning – and yet the war has only been going on for a few weeks. A serious and almost oppressive mood would not go away. When we came out of the church as darkness fell, we saw a newspaper with a big victory announcement. We all went to the newspaper, where the extra sheets were being distributed, still damp with pressure. Ten French army corps had been defeated by our crown prince’s army between Reims and Verdun. That was still a nice Sedan joy. We went home happier now. The victory of Colonel-General von Hindenburg in East Prussia also turned out to be a magnificent feat of arms. We read that 100,000 Russians were pushed into the Masurian Lakes, of which 70,000 men and 300 officers surrendered. The entire Russian northern army has been destroyed.”

“Thank you very much for your last two cards dated 21st and 24th. The post arrives very irregularly. I received the card dated 24th eight days before the other one. I also received several parcels of sweets. Thank you very much for those. A cavalry division has been outside Paris for about eight days. I almost believe that Lothar is lucky enough to be there. He will have experienced more than I have, since I am sitting here in front of Verdun. The Crown Prince’s army is closing in on Verdun from the north, and we have to wait until it surrenders. Verdun is not under siege, but only surrounded. The fortifications are too formidable and would therefore require enormous amounts of ammunition and human lives if one wanted to storm them. Possession of Verdun would not bring us any corresponding advantages. It is just a pity that we are tied up here and will probably end the war here. The battle for Verdun is very difficult and claims a number of lives every day. Yesterday, eight officers from the 7th Grenadiers were killed in an attack.”

MvR writes his mother

Die Erinnerungen der Mutter des roten Kampffliegers Kunigunde Freifrau von Richthofen. Im Verlag Ullstein - Berlin, 1937. p. 18

“We had news of both sons. Lothar is already on his way to Paris with the cavalry division. Manfred is outside Verdun. He’s already been through a lot. He only brought back four men from his baptism of fire – on a reconnaissance ride against the enemy entrenched in the forest. Now he has been entered for the Iron Cross. Lothar also wants to put his ambition into winning this honour. He has only received a single card from home. All our letters, our chocolates and packets of cigarettes have not arrived. How can that be? – But we have no reason to complain. Our sons have got through all the dangers safe and sound, and Lothar has just become a lieutenant. We read about it in the newspaper, which was a pleasant surprise – I received a card from Manfred’s landlady saying that his flat was being rented out elsewhere; I would like to come there soon to dispose of his things…”

“Dear Mum!

I have some good news to share with you. Last night, I received the Iron Cross. How are things in Lemberg? Here’s some advice: if the Russians come, bury everything you want to see again deep in the garden or somewhere else. What you leave behind, you will never see again. You are surprised that I am saving so much money, but after the war I will have to buy everything new. Everything I took with me is gone – lost, burned, torn to pieces by grenades, etc., including my saddle gear. If I should emerge from this war alive, I would be luckier than I am sensible.”

MvR writes his mother

Die Erinnerungen der Mutter des roten Kampffliegers Kunigunde Freifrau von Richthofen. Im Verlag Ullstein - Berlin, 1937. p. 21

“…The war has taken its toll on our sons. I have to thank God that they are still alive. Lothar was wounded on a patrol ride by Nebermann and Bordermann. His horse was badly wounded. Manfred’s entire equipment was torn to shreds by grenades, including his saddlery. He is now saving up – so he writes – to buy everything new after the war. Despite all my worries, I had to smile when I read it. ‘After the war’ – when will that be? But the remark about saving characterises him. He will never attach so much importance to a danger, however exciting, that he forgets his clear, purposeful actions.”

MvR received the Iron Cross

Die Erinnerungen der Mutter des roten Kampffliegers Kunigunde Freifrau von Richthofen. Im Verlag Ullstein - Berlin, 1937. p. 23

“…I have time to ponder, my thoughts always drift in the same direction, the mothers are always with their sons in the field in spirit. I can consider myself proud and happy. Both sons made it to this day safe and sound. A grenade burst on the saddle of Manfred’s horse when he happened to be dismounted on patrol. Nothing happened to him, only a splinter cut his cloak and the bottom of a bullet crushed Aunt Friedel’s beautiful gifts of love into a shapeless pulp. Now a new parcel is about to go out to him. By the way – how can you forget! – Manfred has been awarded the Iron Cross. We are all delighted about this honour…”

“Dear Mum!

The post is about to go out, so I wanted to quickly send you a greeting. I’ve had quite an eventful few days. I almost lost my life, but luck was on my side once again. I was on patrol and had just dismounted from my excellent Charger when a grenade landed about five steps away from me and exploded on my horse’s saddle. Three other horses were also killed. My saddle and everything I needed and had in my saddlebags was, of course, torn to pieces. A piece of shrapnel tore my cloak, but otherwise I was unharmed. I was reading a letter from Aunt Friedel; I hadn’t opened the accompanying package yet, but had put it in my saddlebag – it was crushed into a shapeless mass. I also had Antithesis with me; he got a small splinter in his back teeth – nothing serious.”

MvR almost killed by artillery fire

The Red Baron, The World War I Aces Series Number 1, William & Robert Haiber, 1992, Info Devel Press p. 17

“MvR almost killed by artillery fire; his horse is killed.”

“Dear Mum!

A car has just arrived here, loaded with the first parcels, including two from you to me. It’s the fur coat and a small parcel containing my gloves. The fur coat is magnificent and will be very useful on cold nights. Thank you very much for it. It was very nice that you were able to see Lothar in Posen again. The twenty-two hours of waiting at the station were less edifying, however. I can sympathise with you, as I spend twenty-four hours every other day waiting in the trenches – but for the French. We, the 1st Uhlans, unfortunately have no prospect of ever doing anything else in this war – unless the plague breaks out in Verdun. Lothar got the more interesting part. I really envy him. It’s now in Russia, exactly in the area where I rode my patrols for the first ten days of this war. I would have loved to earn the E. K. I., but I don’t have the opportunity to do so. I would have to run to Verdun disguised as a Frenchman and blow up a tank turret there.”

“Dear Mum!

We are now lying in shifts like the infantry in the trenches, with the French two thousand metres in front of us. It’s quite boring in the long run, because lying there quietly for twenty-four hours is no fun. Every now and then, the only change is a few grenades coming in, which is all I’ve experienced in the last four weeks. It’s a shame that we’re not involved in the big field battle. The situation in front of Verdun hasn’t changed by fifty metres in weeks. We’re lying in a burnt-out village. Wedel and I are living in a

house where you have to hold your nose. We rarely ride, almost never, because Antithesis is sick and my chestnut horse is dead; we run even less. In other words, we don’t get any exercise at all. We eat less well than we used to. As you know, everything sticks to me – so now I’m as fat as a barrel. If I were to ride races again, I would probably need a few courses of treatment before I could get back to my normal weight.”

MvR's mother picks up Manfred's things in Ostrowo

Die Erinnerungen der Mutter des roten Kampffliegers Kunigunde Freifrau von Richthofen. Im Verlag Ullstein - Berlin, 1937. p. 28