Bodenschatz’s testimony

Event ID: 443

21 April 1918

Source ID: 58

“It is 21 April 1918.

Fog and grey ground haze hover over the airfield at Cappy. It smells of frost and spring. The officers of the squadron are standing together, fully dressed. They are all in a dazzling mood. Their laughter sings again and again through the easterly wind. They have every reason to be in a good mood: the great successes of the last few days, the unreserved recognition of their superiors, their fast triplanes, which have proved themselves excellently, the new airfield, where they feel extremely comfortable, everything is once again in great shape, both internally and externally.

This time the cavalry captain exuberantly commands this good mood. He suddenly tips over a stretcher on which Lieutenant Wenzl has laid down for a good nap, and when another tired son of the earth unsuspectingly also lies down for a good nap on the free stretcher, the cavalry captain also tips this young man into the spring muck. In return, some of those who want to take bloody revenge for this private intrusion into their comrades’ right to slaughter attach a brake block to the tail of Moritz, Richthofen’s mastiff, so that the offended creature seeks consolation and recognition from its master.

Again and again the baron’s laughter echoes across the square. They have seldom seen him so purely and loudly amused. And they know that this hunter is actually very happy about the 80th game he brought down yesterday, even if he doesn’t say much about it.

He is also leaving for the Black Forest in a few days with Lieutenant Wolff to indulge in some milder hunting. The father of the fallen lieutenant Voß has invited him to his house. Two tickets are already with the adjutant.

Everyone at the airfield is very much in favour of the commander relaxing a little; if it was one of them’s turn to climb into the sleeping car instead of the triplane, it was him. And there are other people outside the flight area who are also very much in agreement. Higher beings, so to speak, who even sit in the Grand Headquarters. The speed with which Richthofen wrote his firing list was met with great respect and a great deal of esteem: the names Boelcke and Immelmann were harsh examples of where the path of the best, precisely because they are the best, must ultimately lead, must lead under all circumstances. That’s why, some time ago, Lieutenant Bodenschatz was approached to see if it wasn’t possible to get the Rittmeister round, for example, there was a very nice field of activity for him, an inspection centre for all hunting squadrons, where he could make his wealth of experience available.

The cavalry captain laughed in his adjutant’s face as he dutifully tapped him under the hand. “Ink spy?…Nope!!…Stay at the front!” That was the end of the matter. But he didn’t mind travelling to his friend Voss’s father in the Black Forest for a few days.

The east wind swept across the square and they all lifted their heads and sniffed. If it goes on like this for a little longer, the weather will soon be clear and the lords will come dancing.

By half past ten, the easterly wind has pushed the clouds aside and it is clearing. The officers hurry to the aircraft. But the commander slows down a little and says that they should wait with the take-off so that the lords become quite cheeky, then it would be all the easier to get them in front of the cannon. At this moment a telephonist comes running: some Englishmen are flying at the front.

In less than five minutes, the first triplanes thundered over the square. First Lieutenant Bodenschatz strolled slowly to the observation post and glued himself to the scissor telescope. It was around 11 o’clock in the morning. He sees the two tracks of Squadron 11 flying towards the front, one led by Lieutenant Weiß, the other by the commander. They roared westwards along the Somme.

Then he discovers the Lords and it is no longer possible to tell friend from foe. Around twelve o’clock, the squadron flies in again, one aircraft after the other hovers out and lands. Suddenly the adjutant is struck like a bolt of lightning from top to bottom: he stares out onto the field. Richthofen is not there!

He shouts down from his high seat, somewhat anxiously, towards Lieutenants Wenzl and Carius, who have climbed out and are now running towards him. ‘Where is Richthofen?’

Lieutenant Wenzl says sternly: “I’ve got a stupid feeling; we were just over the line and 7 Sopwith with red snouts came over the line, the anti-Richthofen people, the squabble started, they were outnumbered and we couldn’t get a proper shot. The Rittmeister flew on sight and now approached with his chain. But there were already 7 or 8 new lords coming down from above, there was a gun fight, all mixed up, we all drilled each other a little deeper, in the east wind we got more and more beyond, broke off the battle and slept our way back over the lines… I have a stupid feeling. When I flew back, I saw a small plane east of Corbie that hadn’t been there before. I think it was a red plane!”

The men stare at him for a second, then Captain Reinhard, the squadron’s most senior officer, immediately orders Lieutenant Wenzl, Lieutenant Carius and Lieutenant Wolfram v. Richthofen (the commander’s cousin) to show up and scout the area around Corbie for the red aircraft.

The three machines race across the square and go up. They get lost at the top while searching. The lieutenant Wenzl rushes stubbornly and with clenched teeth in the direction of Corbie, he goes down to 2-300 metres and tries to get close to the machine to determine its identity. Instead of one machine, he now sees two standing in that spot. He can’t be sure of anything from this distance, he would have to cross the lines. Under a hail of machine-gun and anti-aircraft fire, he tries, but English single-seaters are already breathing down his neck. Nevertheless, he breaks through on murder and manslaughter and gets closer to the mysterious machines on the ground, when there is a violent chirping in his aircraft. Three Sopwiths come sweeping up behind him. There was nothing more to be done, they were pushing him deeper and deeper anyway, and it was a hunt by hook or by crook. When he reached his own line, the British caught up with him and now he risked the last: at a height of 20 metres, he swept over the German tethered balloon standing there and then along the ground to Haufe. So there is no new report.

In the meantime, the news that the commander has not returned has reached the last man. The people stand around gloomily. Nobody says anything. As soon as Lieutenant Richard Wenzl had taken off, the adjutant put all the air raid officers on the phones. None of them can report anything. Now all the division commands in the section are alerted. The same sentence is repeated again and again in a frantic rush: “Squadron 11 has returned from an enemy flight. The Rittmeister is missing. The men of the squadron report that the Rittmeister is down. Has a red triplane made an emergency landing in your section? Has a red triplane been observed landing on either side of you?” And at the artillery and infantry posts, all the buzzers raise their voices and ask: red triplane, red triplane, red triplane? The order receivers and signal runners stumble hurriedly through the connecting trenches, shouting and passing on notes: “Red triplane, red triplane, red triplane?…All the scissor telescopes, trench mirrors, binoculars, all the eyes of the infantry in the foremost trenches search the terrain: Red triplane, red triplane, red triplane?…Every minute counts, so help us God. If he has made an emergency landing, he must be helped immediately.

Finally, after an unparalleled eternity, the general staff officer of the 1st Division reports the following: The artillery observation centre of Field Artillery Regiment No. 16, First Lieutenant Fabian, had observed the battle perfectly from Hamelin East. Lieutenant Fabian had seen that a red triplane had landed smoothly at height 102 north of Vaux sur Somme. Immediately after landing, English infantry had run up and pulled the aircraft behind the height. The consternation in Cappy is immense at first, but then everyone breathes a sigh of relief. The commander had made an emergency landing and so he was alive.

First Lieutenant Fabian’s report is immediately sent to the Commanding General of the Air Force. The squadron adjutant requests Captain Reinhard’s permission to travel to the observation post of Field Artillery Regiment 16. Perhaps…with the honed eyes of an aviator…the adjutant stares through the scissor telescope for a long, long time, meticulously, almost centimetre by centimetre, searching the terrain, keeping Hill 102 in his lens for a long, long time, asking First Lieutenant Fabian short, quick questions…without result.

At 2 o’clock in the afternoon, the adjutant returns to the airfield, his eyes burning with observation. Some infantry officers have passed on reports, they contain not a word more than the artillery officer Fabian has already reported.

This means that the time within which the cavalry captain could have been assisted somehow and at some point is about over. Now we can only continue to hope that he has landed beyond our lines, at worst wounded, at best unwounded. It is not the first time that he has made an emergency landing, he has even made an emergency landing in a wounded state. In the squadron’s telephone centre, enquiries are pouring in from all sides.

The army high command suddenly decides to take an extraordinary step. The general transmits an enquiry to the enemy in open language. ‘Rittmeister von Richthofen landed on the other side, requesting news of your fate.’ There is no reply.

The Cappy airfield remains silent, listening, dejected. In the afternoon the east wind becomes stronger and cooler. That thrice-cursed east wind! It drives what can no longer resist it westwards, into France. And those whose engines fail are driven. Perhaps this thrice-cursed east wind drove the red triplane westwards, without the east wind it might have… Dreams are idle.

Towards evening, there is nothing left to do but inform Richthofen’s father. He is now the local commander in Kortryk. First Lieutenant Bodenschatz climbs into an observation aircraft, takes the shortest route via Douai and Lille, calls Major Richthofen from Kortryk airfield and asks to be allowed to visit him immediately. In the beautiful town hall of Kortryk, the old gentleman approaches the adjutant through the dimly lit room.

‘I have a feeling something has happened to Manfred,’ he says calmly. The first lieutenant stands stone-faced, searching the major’s eyes: “Major, I have to inform you that Mr Rittmeister has not yet returned from a flight. But all enquiries have led to the hope that he is alive.” The men look at each other in silence. That he is alive? The old officer knows better. And as if lost in deep thought, he says slowly: ‘Then he has fulfilled his highest duty.’

As they take their leave, the old gentleman goes back into the twilight of his room, the adjutant feels as if he is walking into deep darkness. That same evening, the first lieutenant arrives back at Cappy. He hears the half-loud conversations in the mess, sees the crews standing in the square at night and staring up at the starry sky, as if someone they were waiting for so long were suddenly coming down in a gentle glide and declaring everything to be a great joke. There is still a lot for the adjutant to do.

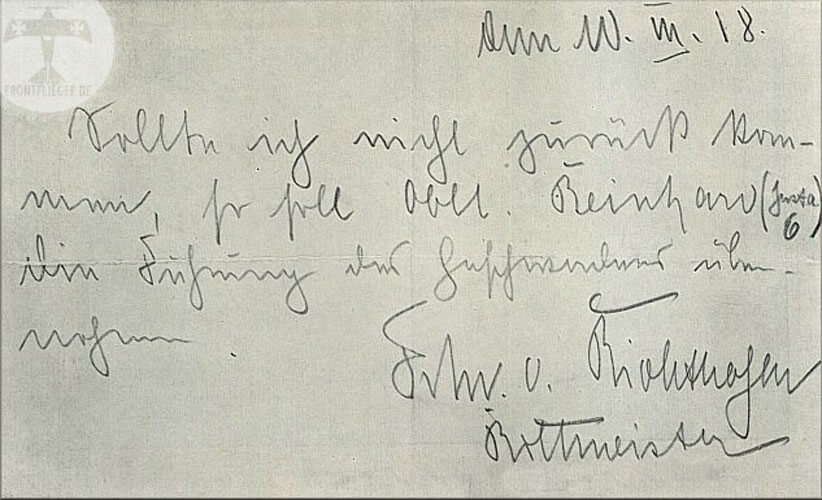

A message is sent to his mother and brother in Schweidnitz: ‘Manfred has not returned from the flight and, according to reports received, has probably landed unwounded on the other side of the lines.’ Captain Reinhard paces up and down incessantly and collapses when the adjutant, dog-tired, throws himself into a chair, suddenly stands up again and takes the iron cassette out of the secret cupboard. He opens it and takes out a grey service envelope, sealed with the squadron’s service seals. The time has come. He thought it was time once before, back at Le Cateau. He opens the envelope. There is a small, no longer quite clean note inside, the adjutant skims it and hands it to the captain.

In Richthofen’s hand, written in pencil, is a sentence: “10 March 18. Should I not return, First Lieutenant Reinhard (Jasta 6) is to take over command of the squadron. Frhr. v. Richthofen Rittm.”

It is his entire will and his entire legacy. It applies solely and exclusively to his squadron. A truly soldierly legacy. Nothing in it concerns his personal existence. There is nothing in it that concerns his personal worries, nothing that needs to be organised in his private life. No soft look backwards, to his mother, to his father, to his brothers. Nothing needed to be organised in his private life. He had no private life. His life belonged to his fatherland, without reservation, without consideration. His life belonged to the squadron. Free and unencumbered, he ascended to every flight. He had made sure that his squadron would fall into the right hands when the dark fate befell him. And he didn’t need to worry about anything else.

But First Lieutenant Reinhard, who has since become a captain, and First Lieutenant Bodenschatz cannot imagine that this modest note is now valid. It is simply not possible that Manfred von Richthofen should have fallen victim to the same merciless law of war to which all men who went to war had sooner or later succumbed. There are exceptions, they kept thinking. And yet he was an exception. He who was so spoilt by the god of battle, so decorated, so protected, could not simply be abandoned by the same god of battle from one hour to the next, betrayed and sold. He must still be alive somewhere.

This hope, to which not only Jagdgeschwader I, but the entire German army, is committed, is fuelled by a strange enemy radio message that was intercepted but suddenly jammed. One could roughly overhear: ‘…famous German fighter pilot Rittmeister von Richthofen was shot down near Corbie and was killed after landing by Australian troops…’ Here the radio message broke off.

We were faced with a puzzle and gradually became a little suspicious. Why was the enemy silent, why did he not immediately announce to the whole world, as he was not at all ashamed to do in other cases, that he had succeeded in striking such a great blow?

Orders were given to question every captured Englishman in detail. But English airmen who were taken prisoner by the Germans only knew that the Rittmeister was dead, others said that a German airman, whose name was kept secret, had been taken to the military hospital in Amiens seriously wounded. Under such circumstances, all hope dwindles.

Rumours and suppositions arose, and these rumours were sometimes bitter, some even saying that Richthofen had been beaten to death by Australian soldiers.”

Comments (0)