MvR writes ‘Reglement für Kampfflieger’

Event ID: 474

Categories:

04 April 1918

Source ID: 28

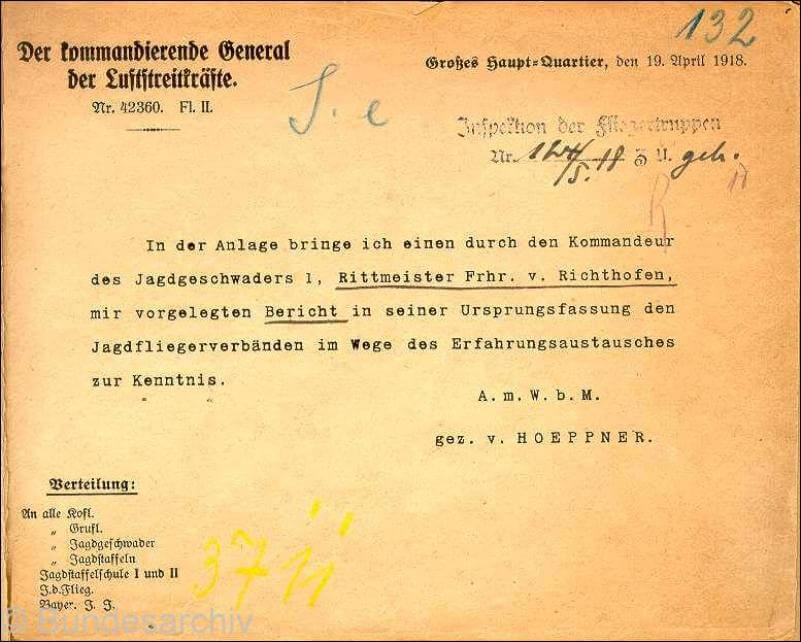

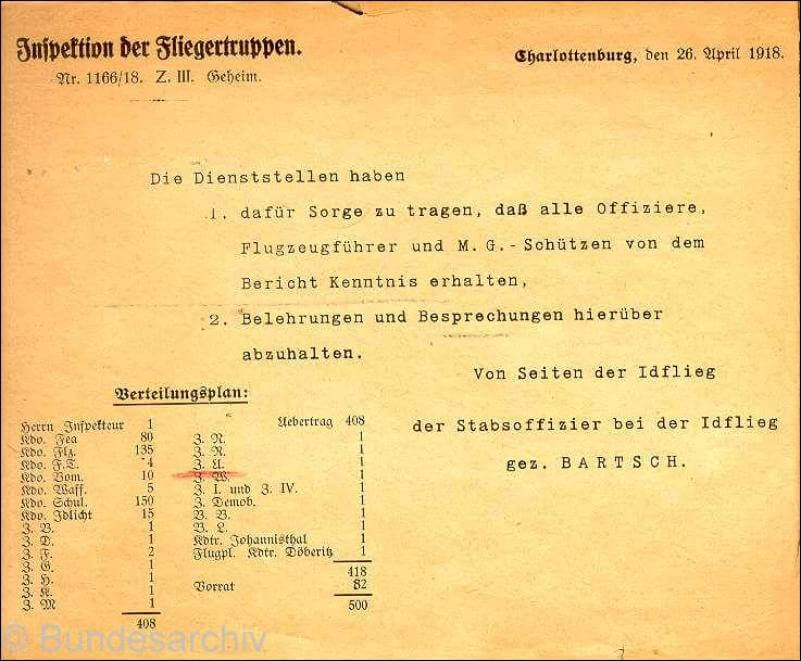

“In April 1918, Richthofen wrote a report summarizing his previous experiences as a fighter pilot and commander. Due to his death soon afterwards, this text was quickly regarded as ‘Richthofen’s legacy’. Initially brought to the attention of the air force through official channels in April 1918, the report was published in 1938 on the occasion of the 20th anniversary of Richthofen’s death by the War Science Department of the Luftwaffe – as Richthofen’s ‘military legacy’, or ‘testament’. A new publication (titled ‘Reglement für Kampfflieger’) was published in 1990, together with Richthofen’s autobiographical writing, under the title ‘Der rote Kampfflieger’, with an introduction by the then NATO Secretary General Dr. Manfred Wörner. The illustration shows the letter from the Commanding General of the Air Force dated April 19, 1918, General d.K. Ernst von Hoeppner, regarding Richthofen’s report, received by the Inspectorate of the Air Force.

Squadron flights.

Boelcke divided his twelve pilots into two chains in the fall of 1916. He made each of them five to six airplanes strong. Six to seven airplanes can best be led and overlooked by a leader and are the most agile. In general, this combat strength is still sufficient today. The Englishman has the most experience in squadron flying and is usually organized in the same way.

However, with very heavy British air traffic, you are forced to work with larger squadrons. I take off with 30 to 40 aircraft, i.e. a squadron flight. (Reason: the inferior German fighter aircraft or strong squadron activity).

The organization of such a large squadron is as follows: The squadron commander furthest ahead and lowest, fighter squadron 1 on the left, fighter squadron 2 on the right, fighter squadron 3 100m above the commander, fighter squadron 4 at the height of fighter squadron 3 as the last behind the commander, distance 150m.

Fighter squadrons follow their fighter squadron leader, fighter squadron leaders follow their commander. Before each take-off, it is essential to discuss what you want to do (e.g. the direction in which you will fly first). The pre-flight briefing is at least as important as the post-flight briefing.

Every squadron flight requires more preparation than a flight within a fighter squadron. It is therefore necessary to announce the squadron flight in advance. So, for example, I say in the evening that the squadron should be ready for take-off from 7 o’clock the next morning. By ready for take-off in this case I mean: fully dressed for the flight, each pilot next to or in his aircraft and not in a take-off house without their flying gear on. The mechanics are ready at their machines. The machines are set up and ready for take-off. Since I can’t know whether enemy air traffic will start at 7 o’clock, it is possible that the whole squadron will be waiting on the field for one or more hours, fully dressed.

The start is ordered by a telephone call (if in different places) or by ringing the bell (if in one place). Each fighter squadron takes off on its own, with its fighter squadron leader last, and gathers the fighter squadron at the lowest altitude (100m) above a point, to the right or left of the commander’s previously indicated flight direction. Then the commander takes off and immediately flies in the direction he has been ordered to fly. The commander flies at low speed until all fighter squadron leaders have taken their prescribed positions. To ensure that the fighter squadrons do not get mixed up, it is advisable to give each fighter squadron a fighter squadron badge at . The commander’s aircraft must be conspicuously painted. The commander must not fly any turns while collecting. He therefore flies as slowly as possible, usually towards the front. Once the commander is convinced that the squadron is complete and that no aircraft are left behind, he can gradually begin to exploit the performance of his aircraft.

The altitude at which the commander flies is the altitude at which the squadron has to fly. It is fundamentally wrong for a commander to fly 200 meters higher or 50 meters lower. In such a large formation (30 to 40 aircraft) the position of the fighter squadron leaders must be maintained throughout the flight. It is advisable, especially for beginners, to determine a seating order within the fighter squadrons. The seating order within the fighter squadron can be so varied that it is difficult to give a specific rule for it. With a well-established chain, there is no need for an exact order. I prefer to lead fighter squadron 11 like the field of a horseback hunt, then it doesn’t matter whether I turn, fall, push or pull. However, if the fighter squadron has not flown so well, it is advisable to keep to the order. If the squadron flight is not successful, then in 99 cases the lead aircraft is to blame. Its speed is determined by the slowest aircraft in its squadron. The fighter squadron leaders flying closest to the commander must not fly so closely that it is impossible for the commander to make a sudden turn; this very often prevents him from attacking and may spoil the success of the whole squadron flight. If an enemy squadron is sighted, the lead aircraft increases its speed. This moment must be recognized immediately by each individual in the squadron so that the very strong squadron does not disperse. If the commander makes a dive, the whole squadron will do the same at the same time; avoid tight spirals and seek the depth in large, wide curves. Unnecessary turns are to be avoided. The chains must change places at every sweeping turn. This creates a great deal of disorder and it may take a long time before the ordered formation is taken up again.

If the commander is unable to perform his duties due to unforeseen circumstances, his deputy must be appointed in advance. A flare pistol signal means that the command has been handed over to his deputy.

It is not advisable for pilots whose engine did not start or similar, to fly after.

The purpose of such a strong squadron flight is to destroy an enemy squadron. Attacks on individual aircraft by the commander are inappropriate in this case. Therefore, such strong squadron flights are only appropriate when good weather is expected. The best thing to do is to get between a broken-through enemy squadron and the front. You cut off its path, fly over it and force it to fight.

The unified attack is the key to success. Once the commander has decided to attack the enemy, he flies towards the bulk of the enemy squadron. Shortly before the attack, he slows down his speed so that the squadron, which has been pulled apart by fast flying or turns, gathers once more. Each individual counts the number of opponents from the moment they are sighted. At the moment of the attack, everyone must be aware of where all the enemy aircraft are.

The commander must not turn his attention to detached enemy aircraft, but must always follow the main body; these detached aircraft will be destroyed by the aircraft flying behind them. Until then, no one from the field has to fly past the commander. The speed is to be regulated by throttles and not by turns.

But at the moment when the commander swoops down on the enemy squadron, it must be the ambition of each individual to be the first on the enemy.

The enemy squadron is torn apart by the force of the first attack and the unconditional will of everyone to fight. Once this has been achieved, shooting down an enemy is only a one-on-one battle. There is a danger that the individual fighters will interfere with each other in combat, giving many an Englishman the opportunity to escape in the turmoil of battle. Strict care must therefore be taken to ensure that the person closest to the opponent only shoots alone. If two or more of them are also close to the enemy at firing range (100m), they must either wait to see if the first attacker is prevented from continuing the fight by a jammed gun etc. and turns away, or look for a new opponent. It is fundamentally wrong and must be ensured that several go down with one opponent. I have seen pictures where about 10 to 15 aircraft joined in the fight and followed an Englishman down to the ground, while the enemy squadron above flew on undisturbed. The one does not support the other by also firing, but keeps in reserve behind it. If individuals have lost altitude in the course of such a squadron fight, they do not wait until one of the opponents drifts off or comes down in the air fight and attach themselves to this already defeated opponent, but they climb flying towards the front and attack an apparatus escaping to the front.

If such a squadron battle is successful and has disintegrated into individual battles, the squadron is shattered. It is now not easy to rally your squadron again. In most cases, it will only be possible to find individual scattered fighter squadrons; the commander circles at the main firing point or above predetermined, well-marked points. The individual ones now attach themselves directly to him. Once he has reached a sufficient strength, the fighter flight is continued.

If the individual members of the squadron can no longer make contact, they must fly home and must not remain isolated at the front in order to avoid unnecessary losses.

It is not absolutely necessary to overfly enemy squadrons. The case may arise where you can no longer overfly very high-flying enemy squadrons. In this case, you keep your aircraft close to the front line, where you assume that the enemy will fly over the front on the return flight. When the enemy squadron arrives, you fly underneath it, trying to lure the enemy into battle by diving at full throttle and pulling steeply upwards. Very often the enemy accepts the fight. Especially the Englishman. He pushes down on individual planes, usually the last ones, and then pulls his plane up again. If an aircraft is attacked in this way, it evades the attack by turning at full throttle, while everyone else tries to outrun the enemy at that moment. Individuals in the squadron usually manage to reach the same altitude as the opponent in this way, and they can try to gain the superior altitude from the opponent by stalling in the turn fight, confront him and bring him down; such fights often last for minutes. The commander has to turn constantly, the squadron gets mixed up and the ordered formation no longer needs to be maintained, instead everyone pushes towards the commander and tries to gain height with their aircraft by turning. Flying straight ahead is very dangerous at this moment, as the enemy is waiting for any moment to attack from the sun without being noticed.

Immediately after every squadron flight, a briefing is the most important and instructive. Everything that happened during the flight, from take-off to landing, must be discussed. Questions from individuals can only be very useful for clarification.

Squadron exercises are not necessary if each individual squadron is well practiced. Squadron flights within the squadrons for training purposes in the line of communication area are not exercises. They can only be carried out on the enemy in order to be instructive.

What I can do with a fighter squadron can also be done by a fighter group (machine gun shooting, signs).

The leader.

I demand the following from chain, fighter squadron or squadron leaders:

He knows his aircraft inside out. Just as the squadron is on the ground, so it is in the air. So precondition:

- Comradeship.

- A strict discipline

Everyone must have unconditional trust in the leader in the air. If this trust is lacking, success is impossible from the outset. The squadron gains this trust through exemplary courage and the conviction that the leader sees everything and is therefore equal to any situation.

The squadron must get used to flying, i.e. not get used to one place or the like, but each individual must be so well attuned to the others that he recognizes by the movement of the aircraft what the man at the stick wants to do, especially when the leader moves to attack or indicates an enemy attack from above to his fellow pilots by strong turns.

I therefore consider it very dangerous to tear up such well-trained pilots.

Within the squadron, everyone has their own special badge on the machine, preferably on the rear part of the tail at the top and bottom. The leader starts last. He gathers his chain at a low altitude and takes the worst aircraft into consideration. When approaching the front, he orients himself over the entire flight operation, enemy and own. He must never leave his squadron unobserved. There will always be this one or that one hanging off. They must be picked up again through turns and throttles.

Flying off the front is not a fighter flight, but one flies to the front, preferably in the middle of one’s section, and convinces oneself of the enemy’s flight operations and, flying away from the front, tries to reach the height of one’s opponent and again, then from the sun, to fly over the front and attack the opponent. The fighter flight therefore consists of advances over the lines and back. If no enemy can be seen over there, there is no point in advancing over the lines.

The attack.

I differentiate between attacks on squadrons and on individual aircraft. The latter is the easiest. I lie in wait for artillery planes, which usually only fly on the other side and not at too high an altitude. I keep an eye on five, six or ten such individual aircraft at a time, observe their altitude and change whether they have high-flying protective aircraft or not, then fly away from the front a little and come back to the enemy lines at a slightly higher altitude than the enemy aircraft I want to attack. As I move away from the front, I have to keep a constant eye on the enemy. The most favorable moment to attack such artillery planes is when the enemy is approaching the front from the other side. Then, taking into account the wind conditions (east-west), I dive at him out of the sun. Whoever gets to the enemy first has the right to shoot. The whole squadron goes down with them. A so-called cover at a higher altitude is a sign of cowardice. If the first one jams, the second one takes his turn, then the third and so on. Two never fire at the same time. If the artilleryman has been paying attention and the surprise has not succeeded, he will in most cases seek the lowest altitude in dives and turns. Then to follow up is usually not successful, because I can never hit a turning enemy. It is also of no practical value just to drive him away; he can resume his activity in five minutes at the latest. In this case, I think it is better to let up, fly away from the front again and repeat the maneuver. I have often brought down the English artilleryman only on the third attack.

Squadron combat on this side is usually more successful, as I can force an opponent to land. Squadron combat on the other side is the most difficult, especially with an easterly wind (in the western theater of war). Then the leader must not get bogged down, otherwise he has to reckon with heavy losses. As long as I can stay on the offensive, I can take on any squadron battle on the other side. If I have a particularly well-deployed fighter squadron, I can also attack a superior enemy from above and beyond. If the single-seater is forced onto the defensive, i.e. if it has jammed, if it has strayed from the fighter squadron or if the engine is shot, the machine is defective, has come down very low, etc., then it is defenseless far beyond against a superior opponent who attacks it vigorously.

The leader may not fly after a squadron that has broken through, but instead soars up between the front and the enemy until he has climbed above him and then cuts off the enemy’s return route. If the enemy squadron breaks through far, there is a danger of losing sight of it. The squadron leader is responsible for ensuring that this does not happen. As I approach the enemy, I count the individual planes. In this way I avoid being surprised at the moment of the attack. During the battle, the leader must not lose sight of his own tracks and the enemy squadron. This perfection can only be achieved in frequent squadron battles. Sight is a prerequisite and the main thing for a chain leader.

How do I train beginners?

Under my leadership, six Pour le mérite knights have shot down the first to the twentieth. Before I let the beginner fly against the enemy, he has to arrange the interior of his airplane in the way that suits him best.

The main thing for a fighter pilot is the machine gun. He must be able to control it in such a way that he can recognize the reason for the jam. When I come home and have jammed, I can usually tell the fitter exactly what the problem was. The MG’s are shot on the stand until they have two parallel spot shots at 150m. The sight is as follows: Once the pilot has personally shot his machine gun on the stand, he practices aiming from the air until he is very good at it.

The pilot, not the gun master or fitter, is responsible for ensuring that his machine gun fires properly. There are no loader jams! If they occur, the pilot is the only one to blame: a well-firing machine gun is better than a well-running engine.

When he belts up, he must ensure that each individual cartridge is precisely measured with a millimeter rule. The time must be found for this (bad weather, at night in good weather).

I attach much less importance to the flying itself. I shot down my first twenty when flying itself still caused me the greatest difficulties. If someone is a flying artist, it does no harm. Incidentally, I prefer someone who can only fly to the left, but can approach the enemy, like the dive and turn pilot from Johannisthal, who attacks too carefully for that.

I prohibit the following exercises over the airfield: Loops, spins, turns at low altitude.

We don’t need aerial acrobats, we need daredevils.

I demand target practice during the flight and tight turns at full throttle at high altitude.

If the pilot is satisfied with all the points discussed, he will familiarize himself with all the types available at the front by means of illustrations.

He knows the terrain without a map and the course of the front line inside out. Large orientation flights, even in bad weather, have to be practiced much more at home.

If it meets the requirements, it flies 50 m to the left behind me for the first few times and pays attention to its handler.

For a beginner it is at least as important to know how to do it to avoid being shot down. The greatest danger for a single-seater is a surprise attack from behind. A very large number of our best and most experienced fighter pilots have been surprised and shot down from behind. The enemy looks for the most favorable moment to attack the rearmost aircraft in a chain. He swoops down on it coming out of the sun and can cause it to crash with just a few shots. It is imperative that everyone’s main attention is directed to the rear. No one has ever been surprised from the front. Even during a fight, you must be particularly careful not to be attacked from behind. If a beginner is surprised from behind, he must under no circumstances try to escape the opponent by pushing down. The best and, in my opinion, only correct method is to make a sudden, very tight turn and then attack as quickly as possible.

The single fight.

Every squadron battle breaks down into individual battles. The subject of “air combat tactics” could be settled in one sentence, namely: “I approach the enemy from behind up to 50 meters, aim cleanly, then the enemy falls.” These are the words Boelcke used to dismiss me when I asked him about his trick. Now I know that this is the whole secret of shooting.

You don’t need to be a flying artist or a marksman, you just need to have the courage to get right up close to your opponent.

I only make a distinction between single-seaters and two-seaters. Whether the two-seater is an RE or a Bristol-Fighter, the single-seater an SE 5 or a Nieuport, is completely irrelevant.

Attack the two-seater from behind at high speed in its exact direction of flight. You can only avoid the machine-gun barrage of the skillful observer by keeping calm and disabling the observer with the first shots. If the enemy turns, I have to be careful never to come over the enemy plane. A prolonged turning battle with a fully maneuverable two-seater is the most difficult. I only shoot when the enemy is flying straight ahead or when he starts to turn. But never from the side or when the plane is on its wing. Unless I try to unsettle him with scare shots (phosphorus strips). I consider attacking a two-seater from the front to be very dangerous. Firstly, you very rarely hit your opponent. You almost never completely incapacitate him. On the other hand, I’m first in the machine gun’s fixed gun and then in the observer’s gun. If I have pushed through under the two-seater and then want to make a turn to put myself in its direction of flight, I offer the best target for the observer in the turns.

If you are attacked by a two-seater from the front, you do not have to run away, but you can try to make a sudden turn under the enemy plane at the moment when the enemy flies away above you. If the observer has not been paying attention, you can easily shoot down the enemy from below. However, if the observer has been paying attention and you are well within the enemy’s sheaf while making the turns, it is advisable not to continue flying in the observer’s sheaf but to turn and attack again.

Single combat against single-seaters is by far the easiest. If I am alone with an opponent and on this side, only jamming and engine (machine) failure can prevent me from shooting down the opponent.

The easiest thing to do is to surprise a single-seater from behind, which often works. If he has been paying attention, he immediately starts to turn. Then it is important to make the tighter turns and stay above your opponent.

If the fight is on this side or on the other side with favorable winds, such a turn fight ends with the opponent on this side being pushed down to the ground. Then the opponent has to decide whether he wants to land or risk flying straight ahead to escape to his front. If he does the latter, I sit behind the one flying straight ahead and can easily shoot him down.

If I am attacked from above by a single-seater, I have to make it my principle never to take the throttle off, but to make all turns, even nosedives, at full throttle. I turn towards the enemy and try to gain the enemy’s height by pulling in the turn and stall him. I must never let the opponent get behind me, and once I have stalled him, the fight continues as in the first one. You can attack a single-seater from the front. Nevertheless, I believe that shooting from the front, even with single-seaters, is a rarity, as the moment when you are facing each other at fighting distance is only a matter of seconds.

General principles.

- When attacking from behind at high speed, I must make sure that I never jump over the slower opponent. If I do, I make the biggest mistake. At the last moment, the speed of your own apparatus must be adjusted to that of your opponent.

- You should never bite into an opponent that you can’t take down through poor shooting or their agile turns when the fight is far beyond and you are alone against a larger number of opponents.

The mission.

In my opinion, the mission can only be determined by a fighter pilot who is also flying; we therefore also need older officers for fighter flying.

In a defensive battle, I consider it best that each group is assigned a fighter group. This fighter group is not bound by the narrow group section, but has the main task of enabling the working pilots to carry out their activities and, in exceptional cases, providing them with immediate protection.

The A.O.K. also has a large number of fighter squadrons, which must be given free rein to hunt and whose deployment is determined by enemy flight operations. By means of air defense officers and a large telephone communication network and radio telegraphy, they are kept up to date on enemy flight operations.

These A.O.K. forces may not be dispersed by protective flights, escort flights or interdiction flights. Their deployment is regulated by the squadron commander in accordance with the instructions of the Kofl.

In breakthrough battles and mobile warfare.

For the breakthrough itself, all the fighter pilots of an army must be gathered under one roof and adhere to a precise order, place and time, but not altitude, so that the troops are directly supported by the air force during the storm and preparation.

If the breakthrough battle turns into a war of movement, then a deployment according to the timetable should definitely be discarded. The British will not fall by standing on the field ready to take off, but only by flying very frequently.

If an airport change is made, each fighter group or squadron must work independently from that moment on, as any telephone connection is virtually impossible. They are kept informed of the situation on an hourly basis by the nearby general commands. If the fighter pilot does not know the exact course of the front, he cannot possibly fight low-flying infantry planes.

He is informed of the air situation by the air defense officer, who follows the movements of the troops and is in radio contact with the squadron commander. The fighter groups must be allowed to act independently with regard to deployment.

The only thing that has to be ordered in the army every day for the next day is:

- The first start at dawn. Reason: This gives the other staff the opportunity to get a good night’s sleep;

- The midday start from 1 to 2. Reason: If I demand a continuous start against the enemy from my fighter squadrons, they need rest for an hour a day.

- The third ordered take-off is the last take-off before nightfall. This is necessary because late in the evening it is practical to stop flying and get your aircraft ready for the next day.In the meantime, free hunting is the only way to provide relief for the infantry.

Free hunting is not to be understood as hunting with night armies or in the salient, but as destroying the enemy, even in the lowest proximity on the infantry battlefield, and flying as often as one can manage with one’s squadrons.

Signed: Baron v. Richthofen.”

Comments (0)