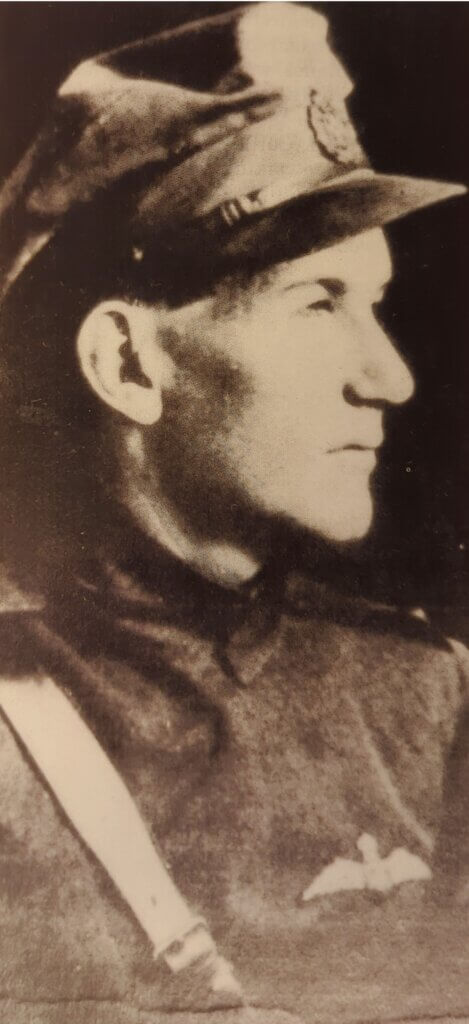

Excerpt of Lewis’ correspondance with Dale Titler.

Event ID: 841

Categories:

20 April 1918

Source ID: 74

ISBN: 0-345-24923-2-195

“Forty-eight years after his fall, D. G. Lewis tells of his brief and almost fatal encounter with the Kaiser’s “Red Devil”, as published in Dale Titler’s ‘The day the Red Baron Died”.

…We were arranged in an arrow formation, Captain Bell leading with Major Raymond-Barker and myself on his right, the two other machines, one on his left and one on my right, then each slightly behind the one in front. The sixth machine brought up the rear. I am unable to remember the names of my other companions in our flight.

Four miles behind the enemy lines we sighted a German formation of 15 Fokker triplanes some miles away, flying at right angles to our direction of flight and above us. They flew in one block. Captain Bell had instructed me before our take-off to keep as close as possible to him and not leave the safety of the formation. I do not think he expected to contact the enemy on that day. His instructions, of course, turned out to be impossible to obey.

Captain Bell was one of the most courageous men I have ever met and from his action that day, I do not think he had any intention, whatever the odds, of returning to the safety of the territory we occupied. Had he entertained that idea he had ample time to turn toward our lines when we first sighted the enemy in the distance. The German formation, however, may have thought that this was our plan, for they manouvered to cut off our excape from behind and swung into a favorable position for the attack.

Although outnumbered three to one, Bell frustrated their strategy by deliberately turning to meet them head-on. Thus the engagement began – the two opposing flights rushing towards one another at a closing speed of over 180 miles per hour with machine guns firing away.

As soon as we had shot past the enemy formation and turned to select an opponent, I knew we had met Richthofen’s famed Circus. The planes were painted all colors of the rainbow, each to personally identify the pilot. One was painted like a draughtboard with black and white squares. Another was all sky blue. One looked like a dragon’s head and large eyes were painted on the engine cowling. Others had lines in various colors running along the fuselages or across them; machines painted black and red, dark blue, gray. There was a yellow-nosed one, too.

Richthofen, of course, led the formation in his Fokker triplane painted a brilliant pillar-box red. Its black crosses were edged with white.

The melee had hardly begun and I beraly had time to single out an enemy machine, when I saw Major Raymond-Barker’s Camel explode on my left. An incendiary bullet must have entered his petrol tank. Then I found myself on the tail of a bright blue triplane which was crossing my path directly ahead of me at the same level. I brought my guns to bear on it and was just about to try to finish it off when I heard the rat-tat-tat of machine guns close behind me, the bullets cracking loud in my ears. Fragments of my machine flew past my face as bullets splintered the cabane center section struts in front of and inches above my head. I forgot all about the man in the blue triplane and took evasive action immediately, twisting and turning to shake my attacker from my tail. As the Camels were wonderfully manouverable planes, for the moment I was safe. I risked a glance over my shoulder and saw that my adversary was flying the familiar all-red triplane – the renowned Richthofen himself!

My first thought was that I should have to be very good and very lucky to escape his attentions so I thought more of keeping out of his line of fire than competing with him.

In engaging the blue machine below me, I had lost altitude, a big mistake in fighting triplanes – or for that matter any enemy machine – and when Richthofen started firing on me, Captain Bell, who must have had a watchful eye open for my safety, chased him off my tail as I sought to escape the machine-gun bursts. Bell’s act was told me afterward and I imagine he “shook” Richthofen with his robust attack, for the red triplane lost height and sight of me for a few seconds and I found myself in a good attacking position. The Baron had slipped below me, and performing a slight turn, I was in favorable position to attack him. My heart leaped in those brief moments and I was excited by the thought: I may bring him down!

As Richthofen slipped into my sights at a fairly close range, I opened fire and my tracers appeared to strike several parts of his machine, although I could not be certain of this as I did not see splinters or fragments fly off his triplane. My Vickers guns were belt fed and fired .303-caliber bullets, with tracer bullets in the proportion of one in 20.

My concern over my own unprotected rear prevailed, however, and in looking out for the possibility of another enemy machine approaching from behind, I failed to maintain a concentrated fire. In a trice Richthofen slipped away from me by performing a steep right-hand climbing turn and I found myself again his target. Again I lost no time in trying to avoid his fire, but he was too experienced for me and seemed to anticipate my every maneuver. He managed to approach quite close – between 50 and 25 yards off my tail – before he began firing.

He delivered a vicious burst with telling effect. Why I was not killed outright I do not know, for my compass, mounted on the dash panel directly in front of my face, suddenly disintegrated before my eyes, sprayin gliquid over my face and scattering splinters and glass fragments throughout the cockpit. One of Richthofen’s bullets struck my goggles where the elastic joined the fram of the glass on the side of my head, and they disappeard over the side. I often wonder if they were found on the ground somewhere in France. Another bullet passed through the sleeve of my coat and still another through my trousers at the kenn, yet none touched my body.

This last burst put me out of the fight, for another one of the Baron’s incendiary bullets set one of my petrol tanks alight. I was not sure which tank -main or emergency – had caught alight, but suspected that the flames, which sought to devour me, had emanated from petrol. Both tanks were located a few inches behind the plywood backrest of the cockpit. As it turned out, only the small, seven-gallon gravity tank was alight, which fortunately did not explode as had one of Major Raymond-Barker’s a few minutes earlier. I switched the engine off as I had always been taught to do when fire was about or threatened and the next thing I realized, I was failling, striving for control of the burning Camel, but never quite getting it. We had no parachutes in those days, so I could not abandon the aircraft…

…I had crashed about four miles northeast of Viliers-Brettoneaux…

…Looking up to see the progress of the fight, I saw the remaining planes of my flight saved from annihilation by the timely arrival of a squadron of S.E.5s. Richthofen separated from his flight and came down to within a hundred feet of me and waved. I returned the wave.

Richthofen also waved to some German troops nearby and I walked a few hundred yards to a trench in which stood some armed German soldiers who had been watching me…

…The mounted officer in charge spoke to my escort, and upon learning that I had just been shot down by von Richthofen, he cantered down the line to tell them this. They all evinced an interest in me as I passed into captivity…

…The next day I was moved to Cambrai Hospital by train…

…This hospital, incidentally, was the one to which Richthofen was taken when he was shot down and sustained a head wound…

… I recall an interesting incident which occurred enroute to Graudenz. We stopped at a railway station and I was taken into a restaurant. I was directed to a table at the far end of the room, and noticed that some German flying officers in my proximity rose from their tables and bowed to me. I acknowledged the saltues. They must have heard that I was shot down by Richthofen and this was their way of paying respect to a fellow pilot. To be honest, I am not sure that this was so, but at the time I strongly felt that this was the reason.

I very much regret that I am comletely unable to say when I first heard of Richthofen’s death and it would not be correct to hazard a guess…

…The number of officers and men who encountered Richthofen is fast diminishing. I was 19 at the time of my meeting with him – the youngest pilot in each of my squadrons. Details of the Baron’s death did not reach me until after I was home, but I always understood that Richthofen was shot down by Roy Brown. …

…Von Richtofen’s combat report gives the impression that I must have been killed in the air and yet it was he who came down to view the remains of my machine. I cannot understand or reconcile his report with his behavior. Otherwise, I have no criticsim of his combat report, which is substantially in accordance with events which took place that day, thousands of feet above France. I was very lucky not to have received one of his 50 bullets in my person, but they certainly did their best to break up my machine.

In all, the air fight was a clear example of the philosophy of some of the more experienced pilots to this type of warfare; with my own fall one day, the Baron’s the next. There are some things about the encounter which cannot be forgotten.

On occasion, when I mentally relive those long perilous minutes when Richthofen sent me, burning, into the German lines, I realize there is no denying the fact that it was a miracle I escaped with my life.”

Comments (0)