209 Squadron – The Second Claim

Event ID: 782

21 April 1918

Source ID: 39

ISBN: 9781904943334

Below are excerpts of Norman Franks’ and Alan Bennett’s book ‘The Red Baron’s last flight’. It contains much more detail than below, and is the ultimate reference on the subject.

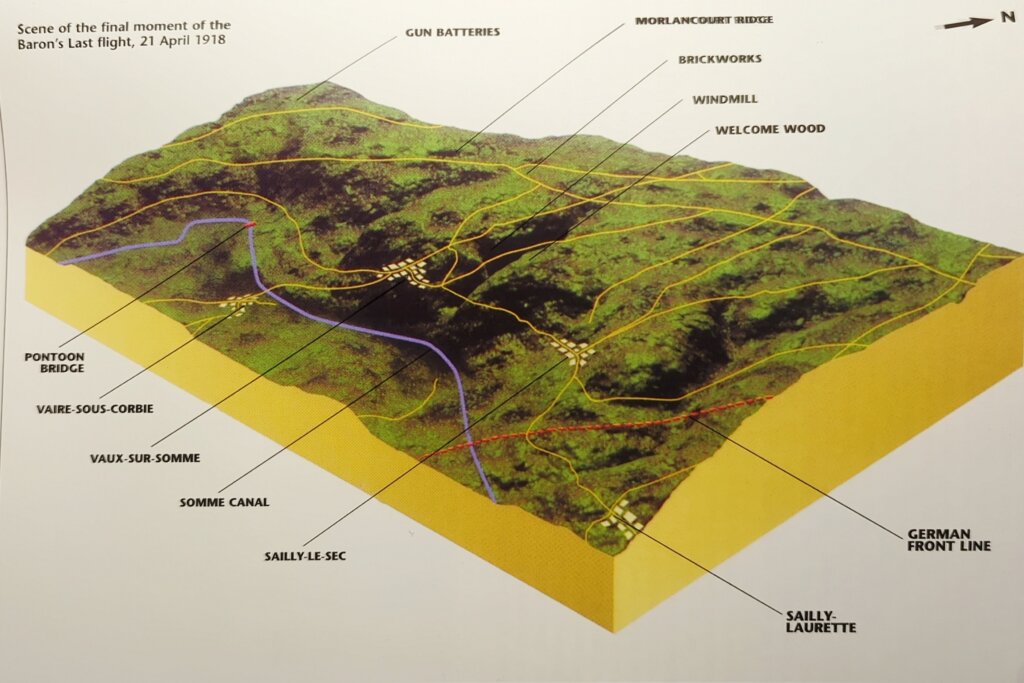

“…Here fate took a hand and the path of Captain Brown’s depleted Squadron crossed with that of Jasta 11 that morning, with von Richthofen leading, they had been joined by a few machines from Jasta 5, Triplanes and Albatros Scouts. At about hours British time battle was joined the area of the town of Cerisy, map reference 62D.Q.3.

Both Brown and von Richthofen had a similar habit which endeared them to their subordinates. After leading an attack, each would detach himself from any combat which followed, climb above it and be ready to go to the aid of any pilot was in a tight spot. Von Richthofen even carried a pair of small binoculars on a cord around his neck for better identification of distant aircraft.

Having re-formed themselves after the engagement with the two RE8s, the Fokker Triplanes were once more patrolling behind the German lines looking for British aircraft. Von Richthofen had rejoined and was at the head of one Kette (Flight), flying with his cousin, Leutnant Wolfram von Richthofen, Oberleutnant Walther Karjus, Vizefeldwebel Edgar Scholz and Leutnant Joachim Wolff. …

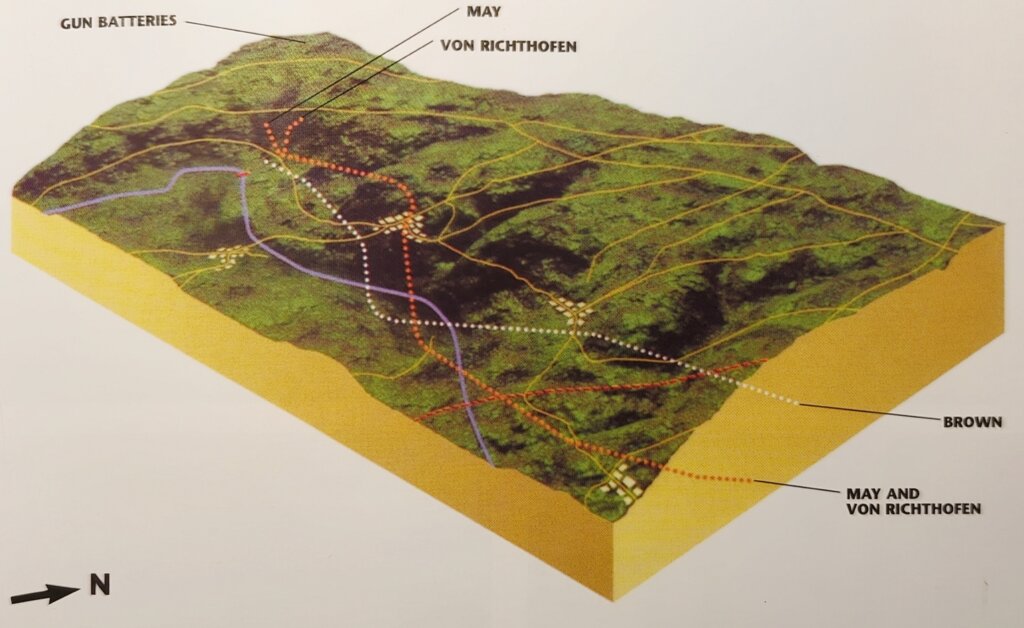

…When the main fight erupted, Wop May, as instructed by his friend and flight commander, Roy Brown (they had known each other back in Canada), edged away but when he saw a Triplane tantilisingly close by, decided to take a crack at it. This turned out to be Wolfram von Richthofen himself trying to stay out of trouble. However, the danger to the Fokker pilot had been spotted by the experienced eyes of the Red Baron, who came down from his ‘guardian angel’ position above the fight to help his young cousin. Those clear experienced and now concentrating eyes latched onto the Camel. There can be little doubt that the Baron, while intent on saving his cousin, was also noting mentally his approaching 81st kill….

…Von Richthofen saw an easy interception and dived to the attack; this required some rapid mental trigonometry. In order to finish his dive in a good firing position behind May’s Camel, he had to aim for a point well ahead of it. Several ground witnesses, mainly those looking east rather than south-east and therefore not into the sun, saw one aircraft and then another dive out of the fight. Although there is no evidence whatsoever of this, it is safe, on the basis of combat airmanship alone, to assume that von Richthofen curved his dive around to the south so as to have the sun behind him in his approach to the Camel. An ‘old hand’, on either side, would not have done otherwise unless he had lost interest in surviving the war…..

…For a reason which will never be known, von Richthofen failed to make a good interception; he came out of his dive too far behind May’s Camel, which gave May the advantage as his machine was the faster of the two.

Taking May’s later testimony as a basis, it may be concluded that von Richthofen came into maximum firing range of May somewhere between Sailly-le-Sec and Welcome Wood. From the Camel’s flight path von Richthofen had probably suspected that its pilot was new to the game and decided to find out for certain. Even with the occasional defective round of ammunition in his belts that mornlng, he could safely tackle an inexperienced enemy. If the Carnel pilot turned out to be otherwise, a Fokker Dr. I Triplane could out climb a Camel any day. He opened fire to see what would happen. An experienced pilot upon hearing the Rak-ak-ak sound of bullets passing close by or seeing the smoke of the tracer, would, without any hesitation whatsoever turn his machine to face his attacker. A novice would spend vital moments looking around to find his attacker who, if close by, was using those same vital moments to correct his aim! If the novice survived the second and more accurate burst of fire, he would probably begin to zig-zag. The urgency with which Brown regarded the situation may be deduced from the airmanship which he now displayed….

….Brown eased his Camel into a 450 dive. adjusted his engine power to obtain 180 mph, which was the maximum safe airspeed, so as not to separate his wings from the fuselage. LeBoutillier later confirmed this angle of dive by saying saw him coming in from the right [of Boot’s position] in a steep 450 dive.’

Von Richthofen’s impression that the Camel pilot ahead of him might be a novice had been confirmed. Upon realizing that someone was firing at him, May swerved his aeroplane and began to zig-zag. The aerodynamic drag of the turns reduced his speed. The Triplane, which was actually the slower aeroplane of the two, now held the advantage and the distance between them began to diminish. May descended lower and lower until he was, in his own words: ‘Just skimming the surface of the water.’….

….All were easy to identify when seen from an altitude of 2000 feet or more. However, from 50 feet above the ground things look very different. Virtually nothing has any quickly recognizable outline or form. The woods no longer have any shape; they are just trees seen from the side. The villages have no shape either, they are just a collection of houses, or ruins of houses. Worse yet, objects pass so quickly that there is no time for a second look just to make sure.

On 21 April there was an additional confusion factor. The wind normally blew from the west. on this morning blowing strongly from the east. Lieutenant May. followed by the Baron, was heading west which means that the wind was hurrying them both along relative to the ground. A pilot who is mentally conditioned to the time taken for landmarks to pass by in a 110 mph aeroplane flying into a 25 mph headwind, can easily be a long way ahead of the place on earth where he believes himself to be when flying with a 25 mph tailwind. The distance over the ground that he would normally cover in three minutes now takes one minute, 44 seconds. With one village looking like another, no distinct forest outlines at this height and no front-line trenches within view on either side of the river (remember, there were only strong points at this stage, frontline trench systems had not been dug), it would be very easy to confuse Vaux-sur-Somme for Sailly-le-Sec….

…Both villages are about the same size, both lie on the north side of the canal, and in both cases the canal has turned to flow north-west. Sherlock Holmes found the fact that the dog did not bark in the night to be of singular significance. Something similar was about to happen, or better, not to happen.

In April 1918 the important difference between the two villages was that Sailly-le-Sec was only half a mile inside Allied-held territory whereas Vaux-sur-Somme was two miles inside. The main night-time supply route to the Allied forces in the Sailly area was the Corbie-Bray road which runs past the Sainte Colette brickworks atop the Morlancourt Ridge. This road was a favourite target for German fighter pilots who regularly strafed it at dawn to catch breakdowns or stragglers, plus the odd attack during the day if cloud cover was favourable. The strong antiaircraft defenses along and nearby this road were very well known to the German Army Air Service. Von Richthofen’s subsequent actions strongly suggest that he took a distant village on the north bank of the canal to be Sailly-le-Sec, whereas it was actually Vaux. On this hypothesis, von Richthofen, in quite unknowlingly having proceeded beyond the genuine Sailly-le-Sec, was in absolute violation of his strictest precept: never to fly low down over enemy territory. He had never done so before and there was no reason for him to do so today. Moreover, in terms of anti-aircraft fire, he was fast approaching the most heavily defended sector for miles around.

In addition to the strong east wind and the badly manufactured ammunition in his guns, another adverse factor entered the situation for the Baron. Presumably because of the hazy air that morning, he was wearing flying goggles with special lenses. From their shape, they probably had been captured from an Allied airman. Their bright yellow double layer lenses considerably improved forward vision (one of the authors has inspected them) through haze, and by eliminating glare made moving objects stand out against a static background. But, being flat, they had disadvantage of eliminating peripheral (side) vision. Like Lieutenant May and Captain LeBoutillier, to see either side von Richthofen had to turn his head considerably; to see directly behind he had to turn his aeroplane….

…The village of Vaux-sur-Somme now appeared right in front of May and the chasing Baron. This should have been the moment for the latter to turn back, but like the singular behaviour of the dog in the Sherlock Holmes story, he did not react to the situation, This tends to confirm that Richthofen had the erroneous impression that the village was Sailly-le-Sec and that he was in the relatively clear area which began a short distance behind the Allied forward defense positions.

From the testimony of the few people who saw the next part of the action, it appears that von Richthofen came within normal accurate firing distance of May’s at about this time. Judging by the events which followed, the most probable explanation why a man who was renowned for his for his accurate shooting failed to dispose of the easy target in front of him is that his left-hand gun was the only one in proper working order and it jammed the instant he opened fire. When the breech-block of the gun was later opened on the ground, it was found to contain a split cartridge case. This was a fault which could not be diagnosed accurately in the air and a pilot could easily expend useless effort in the hope of clearing it. It fits with the puzzlement of some of the ground witnesses as to why the Triplane’s pilot did not take advantage of more than one instance when the Camel was at his apparent mercy. As to why von Richthofen continued the chase, the most plausible reason is that the right-hand machine gun was still operable. However, for the sole two or three rounds it would fire at a time to be effective, he needed to reduce the range considerably and, in the total absence of another hostile aircraft, he still had opportunity to do exactly that….

….Lieutenant-Colonel J L Whitham (CO 52nd Battalion), in his command post in Vaux, could hear the noises of the air battle up above the patches of mist which lingered over the village and nearby canal. Spent bullets were dropping from the sky from time to time. He had a front seat in the Stalls and was about to receive a surprise such as occurs when the stage magician waves his magic wand. Suddenly before his eyes and those of the garrison of Vaux a British biplane followed by a German Triplane appeared at roof-top height. Until then they had been out of sight below the tree-tops along the river and canal banks to the east. The British aeroplane was so low down that it had to turn sharp right to miss the church tower. Some of the surprised soldiers took aim with their rifles and fired at the German machine.

In early 1933, Whitham replied to his friend C EW Bean (a war correspondent), following an enquiry:

‘I am very definite on the point that two ‘planes only came down the valley. A heavy fog or river mist, with a curtain of about 150 feet, had rested in the valley of the Somme for several hours and prevented our view of the air fight which we could hear plainly…towards the east, ie.: over Sailly-le-Sec and Sailly Laurette. Both these ‘planes came from the east and downwards , and they flattened out as they passed over Vaux-sur-Somme, less than 100 feet from the valley level. It seemed certain that both would crash into the spur immediately west of the sharp bend of the Somme where it turns southwards towards Corbie, but we saw the leading ‘plane rise at the spur, closely followed by the triplane. The triplane seemed definitely under control of its pilot as it passed over Vaux-sur-Somme and it is difficult to credit the assertion that the pilot was fatally wounded by a shot fired from the air prior to his passing over Vaux. I cannot say whether Richthofen was firing at the Camel at this stage – the noise of both engines was very great – but I heard machine guns firing from the ground further west down the valley.’

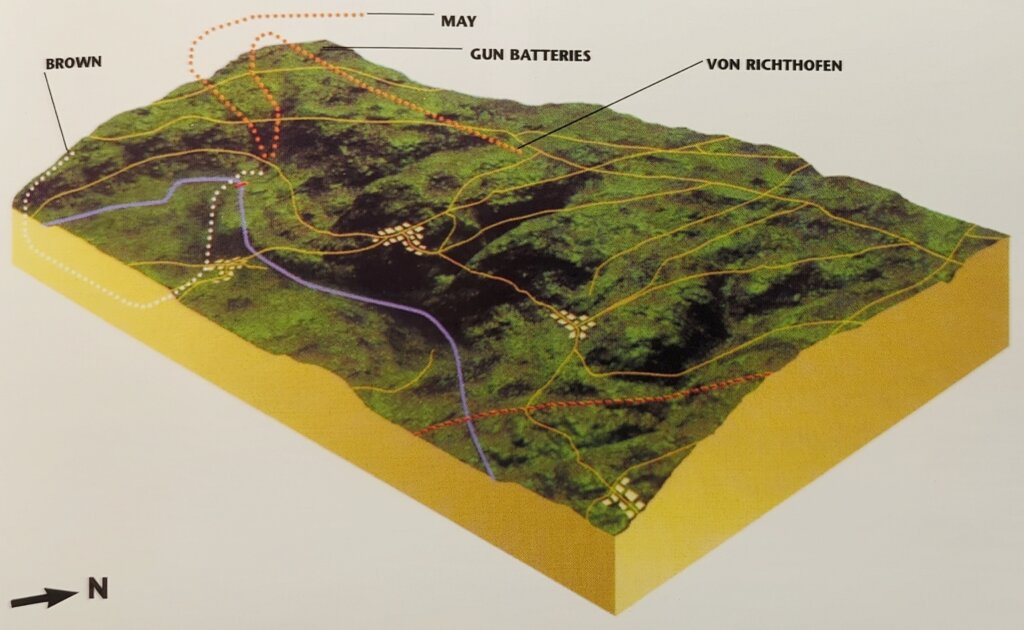

After a short excursion heading north towards the Ridge, the British Camel turned west again just as though the pilot had realised that to make the steepish climb in front of his pursuer was tantamount to signing his own death warrant. The Triplane followed the manoeuvre, cutting corners as it went, and step by step reducing the distance between them. It was obvious that an ‘old hand’ was trying to catch a novice. The puzzle was why the ‘old hand’ had let pass two or three excellent opportunities to down the Camel cool and methodical Baron must have been feeling frustrated and quite busy in his cockpit, which must have reduced the amount of time to glance around and ascertain his exact position. Just moments earlier, the Camel pilot had almost led him into a church tower!

The chase at low-level through the wisps of mist along the south face of the Morlancourt Ridge had begun. One possible reason why von Richthofen made an exception to his normal operational limits and headed deeper into Allied territory is that he saw two Triplanes some distance away and at a higher altitude to his left (south) near Hamelet (not to be confused with Le Hamel) which would provide him with ‘top cover’. Leutnant Joachim Wolff, the pilot of one of them reported having seen von Richthofen. There is no record whether Oberleutnant Walther Karjus, the pilot of the second Dr.l, also saw him….

….Making a montage of testimony of Captain Roy Brown, Oliver LeBoutillier, Lieutenants R A Wood, J M Prentice, J A Wiltshire and Sergeant Gavin Darbyshire, plus Gunner George Ridgway, it is reasonably certain that the following occurred.

Arthur Roy Brown had been in France since April 1917 and been awarded the DSC in October for having shot down four German aircraft. He was on leave over the winter but returned to 9 Naval as a flight commander in mid-February 1918. Since then he had raised his score of combat victories to nine. In short, he was an experienced fighter pilot.

Manfred von Richthofen had survived as a fighter pilot for eighteen months, approximately thirteen and a half of which had been on active duty at the front. Keeping a sharp look-out, having speedy reactions, keeping the dice loaded in his to second favour and a measure of good luck had kept him alive. On this day, the reduced side vision due to his special flying goggles would have forced him to turn his aeroplane in addition to his head to check his tail. During the elapsed time of Brown’s dive and approach he would have done so several times. It is quite likely that Brown saw von Richthofen make a check to the left rear as, with an appropriate deflection angle, he aligned his gun-sights on the Triplane. Whatever happened Brown’s strategy worked well. Von Richthofen, with his vision to the left impeded by the sun at 23° above the horizon, which would have blinded him through the haze, failed to see Brown diving on him. Brown later wrote: ‘I got a long burst onto him’ – which by WWI definition was five to seven seconds. In fact, Brown’s strategy worked too well, for, during his low, high-speed pass from out of the haze, through the wisps of river mist and back into the haze again, he was not visible for very long to anybody who was looking upwards or horizontally to the south-east. Apart from a working party down in the valley, only those who were high enough up to see downwards over the Ridge at a steep angle through the mist, and who were looking that way at the right moment, saw the entire interception.

During such a burst of fire the Camel would have moved somewhere between 175 and 245 yards closer to the Triplane. Allowing distance for collision avoidance, it would appear by calculation that Brown was 300 to 350 yards away from his target when he pressed the triggers. To close the range to the normal 50 yards before firing would have taken seven or eight more vital seconds and could easily have cost Lieutenant May his life. From the tactics employed by Brown, it would appear that his plan was for May to use his superior speed to escape whilst von Richthofen was occupied countering the sudden new danger that Brown posed.

Up on the top of the Ridge just across the road from the Sainte Colette FOP, Private Emery, a trained and proficient anti-aircraft machine gunner, assisted by Private Jeffrey, was gazing upwards at the distant air battle now scattered between Cerisy and Sailly Laurette. Both were hoping that some ‘trade’ would come their way. They prepared their Lewis gun just in case. Together with Lieutenant Wood, in his trench on the brow of the Ridge overlooking Vaux-sur-Somme, they had a clear view to the south around the patches of mist. Gunner Ridgway, who was 20 feet up the Sainte Colette brickwork’s chimney (which in 1918 was not in the present-day position, but further forwards, closer to the road) was mending telephone wires. (Ridgway was not, as sometimes stated, on TOP of the chimney, nor half way up a telegraph pole.) He had the best view of all. He could not only see above and beyond Vaux but also down into the valley beside it. All four men watched the third aeroplane approach from the south-east in a 45° dive. Except for Privates Emery and Jeffrey, who were too low down, they saw the third aeroplane open fire on the German. Due to later reports that the leading aeroplane was an RE8 from 3 Squadron AFC, it was doubtful that all or any of the watchers identified the types or even the nationalities correctly in the early stages.

In late 1937 and early 1938 John Coltman was in touch with W J G Shankland, from Greenvale, Victoria, who was a gunner with the 27th Battery, AIF in 1918. In correspondence concerning whether or not there was a third aircraft in the vicinity. he stood watching the scene south. he stated:

‘I say quite definitely that there was [a third aeroplane] . . . British and German machines [were] engaged in a dog-fight over the enemy lines and whilst manoeuvring for position they disappeared below the crest Of the s 1 01 on which we had our battery position. In a few minutes a Sopwith Camel plane. flying very low, came into view a little to the right of the brickworks which were situated on the top of the slope and about 4-500 yards to our right and slightly in advance of our position. Sitting hard on the Camel’s tail was Richthofen in a red triplane, followed closely by another Camel. The first Britisher seemed to me to ground his wheels. and hesitate as if about to land and then continued on across the valley to safety. Opposite the brickworks the German rose sharply to 200 feet or so, began a right hand turn and nose dived into the ground.

I was one of the first 20 or 30 to reach the scene of the crash. and can still clearly see the tall, closely cropped fair-haired Baron lying on his back amongst the ruins of his plane.’

Once again we have the distant slant view by Shankland. and from his position it is probable that his feeling that May had attempted to land his machine was due to the fact that the Camel did not climb to escape but flew parallel to the ground as the Gunner viewed it, and assumed it was trying to land. An optical illusion?

In one of May’s later accounts of the action he confirmed that at times during the chase down the valley he was so low he could have gone no lower. This supports the witnesses.

There is another account of a witness seeing May’s wheels touch the ground. This came from E E Trinder, an observer with the 31st Battalion AIF, writing to Coltman from his home in Brisbane in 1938. Trinder had been watching the whole action through a pair of Zeiss binoculars, for his job was to report all daily happenings and movements on the Battalion sector and noting map references etc, This morning his FOP was situated on the spur of Corbie [Morlancourt] Ridge overlooking (ie: from where he could see through his binoculars) both the villages of Vaire-sous-Corbie, which was held by his battalion, and Le Hamel, occupied by the Germans.

I watched their progress over the British side of the lines, both planes [sic] firing at intervals, when I was astonished to notice both planes change direction towards our OP. As they came close the British marked plane was only one length and a half ahead of the German plane which was shepherding the British plane towards the ground. As they came within 40 yards of the OP the British pilot endeavoured to land, his wheels on the plane touched the ground on two occasions, but he had too much speed to land, as he certainly would have capsized. He went over the side of the hill for a few hundred feet. The German was on his tail during this landing movement; the British plane then skimmed the grass and rising went directly towards a wood, which was 150 yards from the OP. Immediately on reaching the wood – the planes were no higher than 50 feet – a burst of bullets from a Lewis gun situated in the wood was fired and the German plane momentarily wobbled and then crashed to the ground. The British plane flew straight on and passed over the town of Corbie. I can honestly say they were the only two planes that were seen over the Ridge that morning, and who fired the burst from that Lewis gun I cannot say. If I had known who the pilot of the red plane was at that particular moment he crashed, I would have certainly broke a record to be in for a souvenir.

This seems yet another case of the short appearance of Brown’s Camel below in the valley being hidden by the lip of the Ridge from a viewer higher up, When combined with the mist over the valley, the sun to the south, we can see quite clearly how people standing in different locations and concentrating on the two main antagonists can report seeing contradictory things if interpreted as applying to the chase as a whole.

Another Australian correspondent with John Coltman in late 1937 was Jack O’Rourke, also from Brisbane. Being in another spot, apparently about a mile further to the east than Trinder, he was most emphatic that the second Camel did the damage: ‘anyone suggesting that there was not a third plane in Richthofen’s fatal dive is very definitely wrong. The third plane was on Richthofen’s tail quite long enough to have caused this great airman to go to his death.

I was standing not more than 50 yards from where the pursued Camel flattened out from its life or death dive and could plainly see the pilot looking round to see if Richthofen was following. On looking up for Richthofen I found that his guns were not firing and that he seemed to have changed the angle of his dive and that he had another plane on his tail , His machine seemed to wobble and considerably slacken its speed as the other British plane left him and returned to the dog-fight, This would naturally convey to one that the second British pilot was satisfied he had got his man.

Major H C Rourke MC was another of Coltman’s correspondents, whilst serving at the Royal Military College, Duntroon, Australia in 1937. He atop the Morlancourt Ridge, east of the brickworks, on the 21st, with the 27th Field Battery AIF:

‘I was standing in the mess dug-out on which was mounted an AA Lewis gun. After the battle had been going on for some minutes I saw a Camel dive towards the ground. It was followed at once by the red triplane. As they got near the ground they were both obscured by trees and a ridge to the south-east of the battery. Shortly afterwards three planes (two Camels and the red triplane) came into view from the south-east and commenced chasing one another round the trees. The triplane was engaged by a large number of ground AA Lewis guns including my gun, whenever it was safe to fire. One Camel disappeared early and Richthofen appeared to be getting the better of the other. Finally the last Camel appeared to break off the fighting and fly off in the direction of the aerodrome.

Richthofen manoeuvred his plane round the trees for a short time, as if looking for his opponent, and then flew due west straight up the Corbie ridge, generally above the Corbie-Bray road. He was flying about 200 feet above the ground and was being engaged by a large number of Lewis guns. As he passed over the ridge the nose of the machine was almost pointing straight up in the air, He then dived suddenly and appeared to crash nose first ‘

Up in the sky from a distant slant view Le Boutillier saw Brown make his attack exactly as described on the plaque in the military club in Toronto where the Triplane’s seat, etc. is on view. LeBoutillier stated that he saw Brown’s tracer strike the Triplane but he did not say where, presumably the slant view would not have allowed him certainty. Apparently he said in later life he saw the bullets strike the cockpit area, but one has to wonder if by that time he was adjusting his view to fit the known facts? At the very least the tracer passed by close enough for von Richthofen to see the trails of smoke.

Lieutenant Wood heard shouts from the field kitchen in the trees on the slope below him. Bullets from the air struck the mobile stove; one of them had holed the stew-pot and part of his platton’s mid-day meal was streaming out through it onto the ground. The hungry men must have noticed that the third aeroplane was facing in their direction at that time for they cursed its pilot roundly and in no uncertain terms! This is further confirmation that Brown attacked the Triplane from the south-east; that is on its left side.

As no bullet holes were later found in the tail or the rear of the fuselage, on the basis of probability it may be presumed that some of Brown’s bullets hit the Triplane’s wings and that von Richthofen saw the smoke of the tracer from the others pass by. After the forced landing, one soldier who looked at the Triplane stated that the interplane struts on one side had suffered damage. Unfortunately he did not clarify which side or how he thought the damage had occurred. Whether the Baron heard the Rak-ak-ak sound, saw tracer smoke, heard/ saw bullet holes or was hit towards the end of Brown’s long burst, his subsequent behaviour establishes that he believed he was being attacked from the left. Even if he saw no indication of the whereabouts of his attacker, the position of the sun to his left and the Ridge face to his right heavily favoured the left.

Von Richthofen’s immediate and ingrained reaction would have been to turn and face his attacker who would logically be somewhere up there in the sun on the left and who was most likely correcting his aim at that very moment. To hesitate meant to be shot down. People who have claimed to have fought against him in combat all confirm how quick his reactions were. The first shot fired in his direction and he was gone.

However, on this occasion, being too low down to roll over and dive away, plus the risk of a collision if he turned left to face the attacker, he ‘broke’ sharply to the right.

There were two good reasons for this ‘breaking’ direction. The first was that it would put more distance between himself and the bullets coming his way. The second one was also the reason why Brown stopped firing and began turning left – to avoid the mid-air collision. Other than stories which depend entirely and absolutely upon bullet holes which never existed, no information has been found to gainsay LeBoutillier who claims to have seen the ‘break’. Whilst von Richthofen was occupied, May had been handed an excellent chance to escape. Unfortunately he did not see the chance and continued to zig-zag…

…If von Richthofen had been killed by Brown’s long burst, the red Triplane would have crashed beside the river between Vaux-sur-Somme and Corbie, or certainly on the southern slope of the Ridge. Its engine would probably have still been running at normal power. A wonded von Richthofen could recover control and fly for some time; how long and how well was another matter. Those who query whether he was hit at this stage, either by Brown (who in any event was the wrong side of the Triplane to inflict the mortal wound) or from ground fire from the Ridge, must explain why the Baron not immediately turn south to south-east, towards the German lines, rather than face the climb over the Ridge.

Wounded or untouched, as may be. whilst von Richthofen was completing his evasive action, he would already have been looking for his attacker. He would have noted that the aircraft which had caught him by surprise had overshot at high speed and would not be back for a while. Assuming the Baron had mistaken his ground position, he would have believed that the heavily defended zone between Vaux and Corbie was yet a couple of miles away…”

Comments (0)